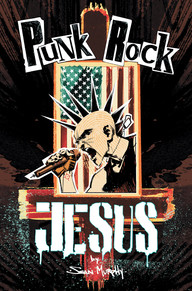

Sean Murphy

2013

The Year’s Work in the Punk Bookshelf or, Lusty Scripts

Brian James Schill

2017

Christmas Eve 2019: a major media company has extracted DNA traces from the Turin Shroud and the teenage winner of auditions to be the new Virgin Mary is about to give birth to the cloned Christ live on camera. Jesus becomes the biggest talk show draw in human history. Until he discovers punk rock.

Sean Murphy’s punk Jesus is born under the world’s gaze and at the

epicentre of Reality TV, a genre emblematic of commodified culture. He is an

excellent illustration (both literally and metaphorically) of what Brian Schill

argues is the essence of punk rock: shame. Shame at the injustice and

suffering of the world the punk has been born into; shame at the recognition

of the punk’s own powerlessness to right that world.

The punk response is to welcome shame, to embody and exaggerate the worst symptoms of society. The word ‘punk‘ itself is an appropriation of a term of abuse with two possible derivations: rotten wood, fit only for use as tinder, and later anything worthless, particularly criminals or prostitutes, later particularly a submissive male homosexual.

In accordance with its name, punk performance is often of abasement, the willing assumption of scapegoat status, as in Iggy Pop’s I Wanna Be Your Dog and his cutting or exposing himself onstage; or the Sex Pistols receiving gobs of phlegm

as badges of honour; or the wearing of bin bags and bondage gear in public. Shame,

says Schill, drives punks to identify with those who are humiliated by the world they

find themselves in. Punks would rather be dead than alive by your oppression.

As it happens, there’s already been a punk rock Jesus. Jesus Christ Allin was born in 1956. His older brother’s first attempts at pronouncing his name stuck and he was known for much of his life as GG Allin. Remembered more for his actions than his music, GG would, like Iggy, cut and expose himself onstage. But whereas it seemed that Iggy aimed to enter into a Dionysian ecstasy which then happened to produce spontaneous self-abuse, GG made abuse the whole point, shitting himself and smearing the waste over his body and his audience, attempting to masturbate and assaulting audience members. He repeatedly promised to kill himself during a show. When he sang Abuse Myself, I Wanna Die, he meant it.

Schill agrees with GG Allin that the logical conclusion of punk shame and humiliation is literal annihilation. The nadir of his interesting book is a chapter on ‘punk love’, a condition that apparently transforms shame ‘into art itself, making of masochism a genuine and aesthetically productive approach to being in a fragmented world in the throes of its own disintegration.’

His examples of punk love are Sid Vicious (suicide attempt, heroin overdose) and Nancy Spungen (murder), Ian Curtis (suicide) and wife Deborah and Kurt Cobain (suicide) and Courtney Love. A clutter of literary theory is employed to tie these deaths to something quintessentially ‘punk’.

In Goethe’s novel of 1774, The Sorrows of Young Werther, the hero blows his brains out in despair of unrequited love. Bootleg copies proliferated, fans dressed as Werther, and there was a reputed spate of copycat suicides across Europe, a phenomenon now known as the Werther Effect. Young men were reportedly found with discharged pistol in one hand, Werther in the other, open at the page describing his death. Some authorities were fearful enough to ban both the book and the costume it described – a moral panic to rival punk. Yet it would be reckless to assume that these suicides were in themselves Romantic. No one became suicidal on reading the novel. People feel suicidal for complex reasons borne of their own sufferings. The expression of such feelings may have been coloured, even bolstered, by Romanticism, but they were not caused by it.

Neither did punk cause anyone’s death. Even considering punks, as Schill does, as people alienated by the modern world who happen to express that alienation in a particular style (precursors noted include Baudelaire, Nietszche, Rimbaud, Dada, Artaud), there is no reason to suppose that they are more prone to self-destruction than any other group. Thorough sociological research would be required to persuade me otherwise. Is the off-stage self-abuse and death of artists in genres other than punk less frequent? Should it be understood as expressing something fundamental about those fields of art?

The remaining possibility, that in a life-as-art fashion a squalid death could, as he says of Sid and Nancy, have ‘ideological clarity’, or be ‘the aesthetic, political and ontological progression that the Woodstock Generation squandered’, is something that I simply reject as an indignity.

Too often Schill conflates the fragmentation and disintegration of an individual’s world with that of the ‘world of emerging markets, perpetual war, and disintegrating communities.’ If ‘punk’s obscenity, self-hate, and destruction [is] the result of its internalization of its abandonment and abuse by its parent culture’, the more proximate cause of an individual punk’s self-destruction will be abandonment and abuse by her parents.

Jesus Christ Allin, like Murphy’s Punk Rock Jesus, was born into an environment of total control, his insane father keeping the family more or less captive in a remote log cabin until GG was five and his mother escaped with her two boys. The extreme behaviour of GG’s live performance was a mirror of his everyday anti-social and self-destructive life, as detailed in GG Allin: America’s Favourite Son (WARNING: the link contains deeply unpleasant material). Rather than exploring a sense of shame at the social order by performing its excesses on stage, Allin was acting out severe psychological damage that was a result of his horrendous upbringing. He died of a heroin overdose at the age of 36.

Though Schill sometimes falls down the rabbit-hole of his own argument, much that he says about punk and shame is persuasive. But to focus on the shame of punk rockers is to speak of punk, and Schill does, as a symptom, something pathological, and to place its creative, productive aspect in the shade. Punk is about annihilation, and its logic does involve death. But the death of punk, not punks.

The proclamation that Punk is Dead was made by the band Crass soon after it was born. Others, such as The Exploited, argue that Punk’s Not Dead. In an interview of Public Image Limited, Johnny Rotten declared that punk was history and didn’t matter anymore: ‘The Sex Pistols was going to be the absolute end of rock and roll …. unfortunately the majority of the public, being the senile animals that they are, got that wrong.’ PiL was a new venture, post-punk, because punk, like the rest of rock and roll, had failed, had become ‘too much like a structure, a church, a religion.’

I once wrestled with this problem myself, wondering how it could make sense that I got immense enjoyment from both thrashing around to Atari Teenage Riot’s Destroy 2000 Years of Culture, and working my way through the literary canon (and un-canon, don’t get me wrong), from classical to modern, that emerged from those same 2000 years of culture. Did I want to destroy or not? But a more acute question than that: the song being itself an artefact of culture, is it telling us that it should be destroyed too? How can punk matter if it’s Dead On Arrival?

Singer with Dead Kennedys, Jello Biafra has said that ‘maybe [punk] should die, because then it can be re-born.’ If punk has to do with the willing assumption of shame and an ambiguous death and re-birth, then Sean Murphy couldn’t have picked a more appropriate archetype for his graphic novel than Jesus Christ. Jesus showed a proper Do It Yourself attitude to his religion, defying the Pharisees, saying his body was temple enough, preaching his own truth, accepting vilification and death. His followers built a church on his rejection of churches.

Through 2000 years Christianity has been reinvented over and over as people have gone back to the New Testament and interpreted it themselves, rejecting priestly authority and forming their own communities of worship, frequently inspired by the voluntary poverty and communal ownership of goods practised by early Christians. Though each new denomination tends to become an authority itself, the development of anarchy as a political ideology has been traced through Christian radicals such as St Francis of Assisi, Thomas Müntzer and Leo Tolstoy. Today, Christian Anarchism is a recognised movement that claims Jesus as an anarchist. This recurring return to the source and re-birth of Christianity has been constitutive, through Renaissance Humanism and the Reformation, of secular, liberal society.

I came to resolve my dilemma about punk’s self-effacement as follows. We are born into a world that existed before us, our parents and our society tell us what it is all about and we, not knowing any better and needing to know something, accept what we are told. When we enter adolescence, we begin to question received wisdom and to develop our own beliefs about the world. At this stage it’s entirely necessary for each of us to reject, to metaphorically destroy, the 2000 or more years of culture that have been given to us. Then we take what we want of it and make something new. Even if what we make looks the same as what we ‘destroyed’ – now it is ours. Punk is an artistic expression of this process, which though acute in adolescence, continues throughout life as everything made new becomes old and must be ‘destroyed’ in its turn, if not by us, then by our children.

Hence the rejection of hero worship and genre limitations of many of the original punks, who prefer to see those that follow them make it new. The confusion over whether punk is alive or dead, or who’s punk and who isn’t, is of the nature of punk itself. So to talk of punk only in terms of abjectness, of the shame for what society makes of us, is to ignore what brings the phoenix from the flames, what allows punks to build an alternative society out of what they have been given, the rallying cry: Do It Yourself.

Ian Mackaye is a universally respected punk icon. Wanting to release a single by his first band, Teen Idles, in 1980 he set up Dischord Records to make it happen. Next, in the hardcore punk group Minor Threat, he denounced the self-abuse of alcohol and drug consumption in the song Straight Edge. He is most famous for the band Fugazi, singing ‘I’m gonna fight for what I want to be’, chastising those who sit around waiting, letting life pass them by ‘because they can’t get up’.

Dischord is still going strong, representing dozens of bands and the DIY culture it is emblematic of: of kids forming bands then figuring out how to play, how to make a record, booking their own tours with cheap and all-ages shows, sleeping on each others’ floors, writing and producing their own magazines – making their life their own. The willingness to constantly question oneself, to reject habit – to destroy one’s old self and do things in new ways – is the productive aspect of shame and masochism. To literally destroy oneself is a dead end.

A perennial touchstone of what is versus what isn’t punk is ‘selling out‘, for which a useful shorthand is signing to a major record label. Speaking to Punk Planet magazine (the second best music magazine I have ever read, Punk Planet died in 2007), Mackaye compares running his band and music business independently to the choices of the Shakers or the Amish. Signing to a corporate music business will access management, marketing, money up front, and much more. ‘People say, “You make everything so hard.” Well, that’s right! People see us and it’s like seeing a guy on the highway in a buggy. “Why does he have a horse and carriage? Why doesn’t he get a fast car?” There’s a reason.’¹

This is masochism of a kind. But as opposed to expressing the shame society heaps on its oppressed by literally harming oneself, this masochism is a matter of turning that shame to pride by taking responsibility for making something better. In 1979 Jello Biafra put himself forward as a mayoral candidate in San Francisco: ‘I felt that if nobody else was going to speak out for … people who weren’t necessarily catering to … business interests, I’ll do it myself.’

As Mackaye says, ‘One aspect of Do It Yourself is that you really have to do it yourself. It’s work!’² And that responsibility extends to all choices. Based on the song, Minor Threat fans started a Straight Edge movement that developed internal rules stricter than any Mackaye had thought of, became intolerant, sometimes militant, and survives today. But Mackaye doesn’t like to see choices he makes himself made rules for others, disavowing Straight Edge as a movement and accepting that for others signing to a major label may be the right decision. The unwillingness to be shackled by what came before, whether in society, punk or his own life, shows through in the music. Minor Threat was instrumental in popularising the Hardcore Punk style that many bands play now, but the innovative guitar interplay and experimental song dynamics of Fugazi left it behind.

Punk dies whenever punks become followers in a crowd, or even followers of their past selves, instead of individuals taking their own lead. Perhaps the same can be said of Christianity. Sean Murphy’s punk Jesus learns this when his inflexible anti-religious crusade itself becomes a limitation. ‘Punk ain’t no religious cult / Punk means thinking for yourself / You ain’t hardcore when you spike your hair.’

And yet Myanmar’s Rebel Riot, whose look and sound is highly derivative of what we could now call traditional punk, are a powerful argument that punk isn’t dead. In the face of shame heaped on them by their society and families, their singer Kyaw Kyaw says, ‘I choose to be a punk. It’s my way of life and gives me lots of energy and freedom’. Rebel Riot formed after seeing protestors murdered in the streets by the military. ‘We didn’t know how to fight, but we could make music.’ They do more than that, feeding the homeless and running a project to give children books. Raising a rival to Punk Rock Jesus, Kyaw Kyaw tells us My Buddha Is Punk, disdaining religious rules and focusing instead on what is in his own heart.

Punk can be resurrected, whether as something fresh and unconventional or in all it’s mohawked, three-chord glory, whenever people consciously make it their own. Some cynics like to say that punk died in 1977. That’s because they got old and punk died to them. The young will make the world new in whatever way they choose, and if their rebellion seems gauche and naive, that’s because their elders thought it was enough to have a revolution once and then leave it at that. With any luck the young will be braver, will know how to destroy and recreate everything they touch, and to do so even as they age. The point of punk is to be born again, to live a perpetual second coming, to live at year zero, to be permanently post.

¹ We Owe You Nothing: Punk Planet: the collected interviews, edited by Daniel Sinker, p 20.

² We Owe You Nothing: Punk Planet: the collected interviews, edited by Daniel Sinker, p 19.

Traveller your footprints are

the only path, the only track:

wayfarer, there is no way,

there is no map or Northern star,

just a blank page and a starless dark;

and should you turn round to admire

the distance that you’ve made today

the road will billow into dust.

No way on and no way back,

there is no way my comrade: trust

your own quick step, the end’s delay,

the vanished trail of your own wake,

wayfarer, sea-walker, Christ.

Don Paterson/Antonio Machado