White Sands

Geoff Dyer

2016

This is a travel book, apparently. It proceeds in gonzo style (with a disclaimer that not every detail is strictly factual) as though Hunter S. Thompson mellowed with age, taking up tennis and gentle philosophic musing in place of hell-raising and substance abuse. Which he didn’t.

It’s a diverting exercise to imagine what Dyer’s editor at, for instance, The Financial Times made of his copy on a trip to Norway in search of the Northern Lights. Not only did he not see the Northern Lights, he despised every moment of the perpetual gloom and perishing cold of the Norwegian winter.

Aspirational travel supplements do not tend to find their authors writing of the latest hot ticket destination, in blackly comic vein: ‘It was miserable being in our room, but it was better than not being in our room.’ Nor are many holidays sold and advertisers appeased by descriptions such as ‘this ghastly place’ or ‘this fucking hellhole’.

A Hollywood Tour

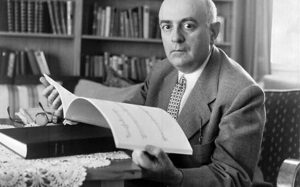

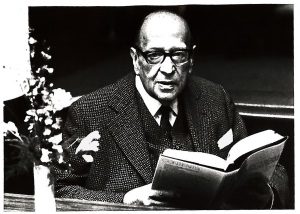

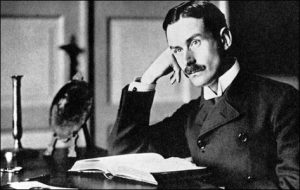

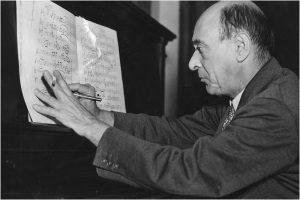

A chapter written for this book, rather than first for the editor of a periodical, recounts a more enriching experience. It tells of one of a series of visits Dyer undertook as a sort of pilgrimage. These were to the homes of European cultural heavyweights such as:

|

|

||

Homes in the suburbs of Los Angeles.

Among the uprooting effects of the rise of fascism in Europe was this migration of intellectuals, many of them Jewish, to the safe haven of the USA (where Christopher Isherwood, another artist estranged from Germany by Nazi rule, joined their social circle). These intensely serious artists and philosophers, some of them explicit critics of capitalism and mass produced culture, found themselves living under the sign of Hollywood.

What it is that we find compelling about a place that someone we admire was in, even if there’s no trace of them now? A friend of Dyer’s is the Slow Paparazzo, snapping places where film stars were a few minutes ago. Does the apparent futility of the exercise reveal the emptiness of celebrity culture? Or heighten the sense of its magic?

Dyer acknowledges his own fanboy status, focusing his account on the trip to Adorno’s old house. Adorno was a philosopher and cultural critic whose work might be described as ‘difficult’. Whether difficulty is a virtue or a vice depends on your perspective, and Dyer recalls his younger days, when having read Adorno was a badge of honour in student circles. And even now he relishes the fact that there is no visitors’ centre, no blue plaque on the building; that few, if any, of the passers by are likely to have heard of Adorno, let alone know that he lived in this place.

The state of Germany purchased Thomas Mann’s one-time California residence in 2016, and for all that preservation of the building and its history is now ensured, no doubt Dyer will be glad that he made his pilgrimage before a path was beaten to its door.

Places Temporary and Final; and Finally Temporal

What it is that attracts us to (or repels us from) certain places, what invests places with significance, is Dyer’s concern throughout. He quotes D.H. Lawrence: ‘some places are temporary on the face of the earth … some places are final.’ Some places are designed to feel final. The Land Art movement of the mid-twentieth century created large scale works in the rural landscape, reminiscent of ancient structures such as Stonehenge and the Nazca Lines.

Dyer describes visits to two Land Art pieces. Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty stands in the Great Salt Lake in Utah, sometimes submerged under its slowly shifting waters, sometimes emerging encrusted in crystals. Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field is an array of 400 steel poles in a one mile by one kilometer grid in the desert of New Mexico. Despite the army of lightning rods, lightning strikes are in fact rare (if, possibly, marginally more frequent than elsewhere). Dyer contrasts the immediacy of an electric bolt from the sky with the calm and extended sojourn required to experience The Lightning Field.

To obtain that experience you must stay the night in a cabin on the site which holds only up to six people and must therefore be booked well in advance. You must leave your car in the nearest town and be driven half an hour to arrive in the afternoon when the light is overhead and uniform, and the steel poles unremarkable.

Later, as the sun goes down, the light catches the steel tips, which sparkle ‘as if stars had perched on them’, the light creeping along the poles until they are ‘glowing … like a fence that could keep nothing out, that let everything through.’ The poles disappear into the night. Then, up at dawn, the sun rising, again ‘the tips of the poles … blink and twinkle’ until to their full length they are ‘stark and golden’.

Dyer concludes: ‘this is not a piece of art to be seen but … an experience of space that unfolds over time.’ The journey through space may be over, but we can still be on our way, even while we’re there.

Gaugin’s Gone

Elsewhere Dyer is thoroughly bored on a trip to Tahiti to see where Gauguin lived so he can write about the painter for the New Yorker. What to Gauguin was exotic and ‘savage’, while pleasant enough, has been package-holidayed to within an inch of its life. A visit to the great man’s grave is a ‘non-experience’.

Overall underwhelmed, Dyer develops a desire to go to the Polynesian islands not on his itinerary, which seem just that bit more idyllic in the brochures than those he visits. He dreams up a version of Genesis in which the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil delivered anti-climax: Adam and Eve wondered if there weren’t other fruits on other trees that would live up to the promise of forbidden billing. ‘They even began to suspect that paradise itself might be somewhere else.’

Musing on the big questions follows: Why are we here? ‘We are here to wish the food was better and to be afflicted by the torment of heat rash … We are here to buy presents for our loved ones … We are here to be bored rigid and then to wonder how it was possible to be so bored. We are here [at the] airport to feel … that we are glad we came even though we spent so much of our time wishing we hadn’t … We are here to go somewhere else.’

Just as The Lightning Field was an experience of space unfolding over time, so again, in the elusive medium of time, the space right where we are can be changed without our moving from it. A place that, in the middle of our experience of it, was boring, can become a place the experience of which we were glad to have. Dyer imagines himself ‘a traveller from a thousand years hence, come back to puzzle over the significance of this place.’ Taking this perspective sharpens his attention on what people have made of the place he is in, cutting and building meaning into the landscape.

Who was here before us, and why? The answers to these questions create places, as the Slow Paparazzo knows, and ‘much geographical travel is actually a form of time travel’. Dyer’s insight echoes that of Rabindranath Tagore in My Reminiscences: ‘In the streets of Calcutta I sometimes imagine myself a foreigner [or why not a time-traveller?], and only then do I discover how much is to be seen. The hunger to see properly is what drives people to travel to strange places.’