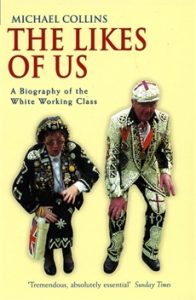

The Likes of Us: A Biography of the White Working Class

Michael Collins

2004

The working class of the united Kingdom in all its football hooligan, white van driving, Croydon facelifted, stereotyped non-glory is the culture Michael Collins grew up in, and in this book he is determined to give us a truer perspective than I just have – to show something of what it is like from the inside.

The book is a series of digressions from the history of his own family, up to and including himself, and that of the Southwark streets in which they lived. This makes it an uneasy mix of social history, family history and memoir, not quite fully any of these and so lacking rigour – though bursting with energy.

And energy is what many others have seen as belonging to the working class. Whereas the youthful socialites of early twentieth century America dared to go to jazz clubs and dance with black people in order to feel free and bohemian, the young iconoclasts of the UK upper classes slummed it with the urban poor for a taste of an apparently more vibrant and authentic life. Jessica Mitford, the communist of the Mitfords, was among the more notorious slummers. She and other well-meaning heirs of fortunes and Oxbridge graduates moved south of the river Thames to live in working class neighbourhoods.

In the UK it was only latterly that the virtues of ‘primitive’ energy were projected onto ethnic rather than working class cultures, onto the rasta rather than the cockney. Collins is alert to the subtleties of the positive stereotypes held by bohemian youth, which, while they at least promote engagement, are the flip side of the coin to the bigotry of their parents.

This shifting of sterotypes suggests that the lightning of prejudice will strike at the nearest conducive point. Collins similarly links the moral panics sparked in the 1890s by hooliganism (a term perhaps derived from an anti-social Southwark family, the Houlihans), in the 1950s by ‘cosh boys’ (who made weapons of passenger straps liberated from Bakerloo Line carriages), and in the 1970s by mugging. The first two were crimes associated with the working class, the last a code word for the crimes of the young black man: all earthed middle class fears of the lower classes they exploited.

I was sympathetic when reading the book: I agree that the working class is stereotyped by other classes – those who dominate political and media organisations, and so whose stereotypes are pervasive. However, on reflection the central argument seems vague and self-contradictory. Written as history with a personal touch it would be interesting and diverting, and if not academically rigorous, capable of bringing us closer to the people it is concerned with. But the polemic pulls it back.

The preface leads with discussion of media commentary surrounding the murder of Stephen Lawrence, which at times conflated the racism and violence of the murderers with a certain class: the working class. This is a high stakes way to enter the conversation, and with it Collins leaves himself with no room for manoeuvre. If you’re going to use one of the most notorious cases of racism in recent times as a jump off point to complain about bigotry against your own group – the group from which the aggressors in the case came – well, you’d better tread carefully.

Unfortunately, Collins does here and there put his foot in it. He sets out to show that historically the working classes have suffered a lot, and this is persuasive. But he drops in quotes comparing the lot of nineteenth century labourers with that of slaves: it is ‘to be a despicable hypocrite, to pretend to believe that the slaves in the West Indies are not better off than the slaves in these manufactories.’ While drawing attention to the suffering of the proletariat is an excellent idea, this quote is hyperbolic and clearly untrue. Collins offers no comment on it. The apparent implication is that if the working class suffered as much as slaves, then prejudice against the working class is as serious a problem in Britain as racism. And this is not credible (sufficiently incredible that some may be rolling their eyes at this point).

The overall theme of the book is reprised in the more well-known Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class by Owen Jones, published in 2011. Collins has reviewed Jones’ book, sadly beginning with the petty comment that it is ‘outmoded’ as the phenomenon of ‘chav’ belonged to 2004, which, coincidentally, is the year his own book was published. His main objection is that Jones is writing from and for his own left liberal middle class. Though Chavs aims to counter the demonization of the working class, Collins thinks it offers patronising political solutions which are themselves based in stereotypes.

The review of the no doubt irritatingly successful later book highlights issues with which Collins struggles in his own. Collins paints his working class as uninterested in either communism or fascism, being simply a community for whom the country is an extension of the street. These are ideologies foisted on the working classes by the middle and upper classes. Change is through ‘evolution rather than revolt and upheaval.’ What politics the working class does have appears in this view to be ‘just getting on with it’, or perhaps that old favourite ‘common sense’. Foregrounding neither his own politics, nor those of his class at large, these remain implicit and confused. Little consideration is given to the possibility that politics among such a large group might be divergent. And this in a book which won an Orwell Award, given for political writing.

A striking aspect of the book is the employment of arguments that post-Brexit and post-Trump are familiar on the far-right (to give the alt-right their proper name): the increasing prominence of identity over class politics; the clash between patriotic nationalists and ‘citizens of nowhere’; and the denigration of working class culture in favour of multi-cultures. Unfortunately, his arguments hang their hat on no political, social, economic – in short on no theory at all, leaving them untested assertions. Collins seems to distrust theories as things that non-working class people have.

Collins asks that working class concerns about immigration should be listened to without knee-jerk claims of racism, but that privilege is not extended to others. By the end of the book, the majority of his Southwark working class community, having benefited from the post-war boom, have moved out to the suburbs of London. Though they have become more affluent, they retain their cultural markers and Collins complains, based on no obvious research, that they are not accepted by their new, traditional middle class, neighbours. Perhaps this middle class has legitimate concerns about newcomers who fail to integrate into their culture? Perhaps this middle class is in the main welcoming and unfairly maligned by stereotypes of stuck-up-ness?

More damningly, Collins, having moved away from Southwark along with many of his generation, revisits it, falling into much the same cliched approach to its new inhabitants as he has argued against elsewhere. He deplores the focus, in discussion of the working class, on crime, squalor and misery: the proclivity to ignore the prosaic happiness that exists even in difficult circumstances. But describing a reunion with old friends he uncritically reports being told that if he doesn’t keep driving he’ll ‘get mugged’; that the area can no longer change for the better because ‘it’s some of the dregs you’ve got here now’; and refers to ‘scenes of shootings and stabbings’ and other criminal acts.

We are not told, but perhaps are intended to assume, that the remnants of the old respectable working class find themselves left to rot in a declining corner of society. Perhaps that is in part true, but little attempt is made to analyse why things may have changed, and none to inquire after these ‘dregs’ – are they the last of the working class, or are they, to use a loaded word, immigrants? How sensible is it to draw a clear line between those two groups?

Knowing Collins only through this book, I find it a shame to harp on what I see as his shortcomings in the politics of race. His observation that the working classes are those who are closest to immigrant populations – living, working, and loving with them in greater proportion than others – is pertinent, and it isn’t to be supposed that demographic change can happen without friction. He rightly points out that those who criticise the race relations of others often do so from the sidelines, as it were, while getting starry-eyed over the exotic other.

The Likes of Us is worth a read for its historical and social content, but with an eye to be kept closely on its subtext. Collins is not far-right, but he does not set out a political context for his views and many of them have now been co-opted by those who are. A telling blind spot in the subtitle is the descriptor ‘white’ working class, which I have avoided. It is clear who he means, but they are white only versus black, and it is white people who, historically, have made skin colour a significant distinction. White working class immigrants – Polish plumbers, to pick out another stereotype – are not the white working class that Collins means. Black pride would be meaningless without racism, and if the working class of the UK have had the stigma of racism unfairly foisted upon them by the wealthy, then solidarity would be a considerably better defence than ‘White Pride’. ‘The white working class have never needed to define themselves or be defined before’, says Collins. I would suggest that they do not start with whiteness.