The Master of Go

Yasunari Kawabata

1972 in translation by Edward G Seidensticker

A thousand years ago the aristocrat and lady-in-waiting of the Empress in the Imperial Palace of Kyoto, Japan, Murasaki Shikibu, wrote The Tale of Genji, a candidate for the first story in novel form. In Chapter 3, Utsusemi, our hero Genji is trying to catch a glimpse of a woman he is infatuated with and gleans that ‘The lady from the west wing came this afternoon. They are playing Go.’

The game the two ladies played was already over a thousand years old, originating in China in some form, somewhere, before the first written reference remaining of 448 BC. Chinese, and later Japanese, gentlemen were expected to be accomplished in four arts: painting, calligraphy, music, playing Go.

Genji, eavesdropping on his paramour, is pleased that she ‘did not seem to be dull either, because near the end of the game, when the contest was on for the last unclaimed territory, she seemed quite clever and keen.’ The anthropologist Marc L. Moskowitz, in his study of Go and formulas of masculinity in contemporary China, traces the historical belief, continuing to the present day, that the game develops the intellect and teaches courtly politeness.

‘No art or learning is to be pursued half-heartedly,’ His Highness replied, “but each has its professional teachers, and any art worth learning will certainly reward more or less generously the effort made to study it. It is the art of the brush and the game of Go that most startlingly reveal natural talent, because there are otherwise quite tedious people who paint or play very well, almost without training.’

The Tale of Genji – Murasaki Shikibu

The implication of the Emperor (in the book that meant the most to Kawabata) is drawn out by Moskowitz, who explores connotations of Go that reach beyond a feather in the cap of cultivation. Not only talent, but the spiritual resources of the player can be revealed by their moves. For centuries Go has been associated with astrology and divination, as well as Zen Buddhist inner discipline. In Kawabata’s novel, the narrator wonders, watching the Meijin, the Master of Go, ‘was I watching a passage to enlightenment as the soul threw off all sense of identity and the fires of combat were quenched?’

Moskowitz, again:

‘the highest level of play was traditionally thought to be an aesthetic art form that connected to larger spiritual forces. Often called a “hand conversation” (shoutan) winning or losing was thought to be secondary to creating a harmonious balance on the board.’

In The Master of Go the players become ‘ghostlike’, their placement of pieces on the board striking an ‘unearthly’ tone, and when the tension of their play rises ‘Demonic forces seem […] lost in horrid battle.’ The game is fought over several months, with hours at a time taken to make a single move, bodies wracked by the intensity of concentration, death stalking the board.

Legend tells of a woodsman who, returning from a long day’s work, happened upon two venerable monks playing Go. When he stopped to watch for a moment, putting down his axe, the elegance of the moves was so marvellous that he stayed, entranced, until one of them looked up and wondered whether he shouldn’t be going home. Noticing the sun was setting, the woodsman reached for his axe, but found only the blade, the rotted remnants of the handle alongside. Rushing home, there were only empty rooms, scattered leaves, dust, and the desire to be back with the two immortal beings and the grace of their Go playing.

One day in the heavenly kingdom, a thousand years in the realm of mortals.

When a game of two opponents is yet unfinished, nothing else has meaning.

A woodsman returns on his path, an axe handle has been eroded by the wind.

Only a lone cinnabar bridge remains.

Lanke Shi – Meng Jiao (758 – 814 AD)

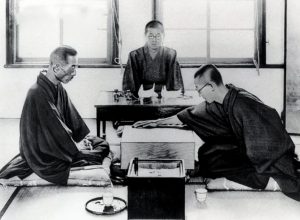

The impression given so far, though – that this novel might be a gothic melodrama – is at best partial. In fact, it is close to what is now called creative non-fiction. In 1938 Kawabata was employed to report on the match between Honinbo Shusai, holder of the title Meijin, and the challenger, Kitani Minoru, by the newspaper that sponsored the bout.

Shusai, the ‘invincible Meijin’, at the end of his long career, had never lost a title match. In deference to his age it was agreed to play sessions at intervals of five days, each player having a twenty hour time limit. It was always going to be a long game, and each player did indeed, here and there, deliberate for hours over a move. Shusai’s serious illness some way through meant that the conclusion wasn’t reached for six months.

Kawabata, on the other hand, jumps straight to the conclusion. In the first chapter, we learn that the Meijin is dead, in the second, that he lost the game. While the novel is substantially based on Kawabata’s serial reports, and has much of their journalistic quality – commentary on moves, character studies, and anecdotes about the players – this move totally undercuts the original context of the writing. Instead of waiting for updates on the week’s session, anticipating and discussing the plays to come, which player has the advantage, the reader knows already that loss and death are inevitable.

For the year 2023, the year that I write this, Lionel Messi was recognised as the best football player in the world, winning his eighth Ballon d’Or. This was largely in view of Argentina, with Messi in the side, winning the World Cup, his club achievements being poor by the standards of his younger days.

Despite this generating uncharitable comments below news articles, (‘Apparently he has won it next year too…’; ‘Ballon d’Or winner in the year 2040: Lionel Messi at the age of 70 for the 44th time.’) the award was widely anticipated and welcomed as fitting for the fairy tale curtain call of a wonderful career. Everyone knew that Messi, age eating away at him, was not playing at the sublime level of his peak. Few begrudged the bow to past glories allowed by his last hurrah in blue and white stripes.

‘In the world of competitive games, it seems to be the way of the spectator to build up heroes beyond their actual powers. Pitting equal adversaries against each other arouses interest of a sort, but is the hope not really for a nonpareil?’

These words of Kawabata have a place amongst the stats and analysis, the cold, hard logic of competition, and behind it the colder, harder logic of money: football still has room for romance.

The romance of the untouchable, the consummate, the all-conquering player is felt in Go too, and status has often been conferred on an honorary basis. The title Meijin was given for a lifetime and there were those who preferred to maintain its dignity by abstaining from the sort of competition that might make it appear ill-suited.

At least up until 2013, in China, a country of 1.3 billion, twenty players a year, mostly teenagers, were awarded the rank of professional, so gaining access to the most prestigious competitions. The rank is kept for life, leading to situations in which a professional who chooses a new career in some other field, Go becoming a hobby, will always be ranked higher than an amateur who makes their living through prize money, won at times against professionals in open tournaments.

Once their rank was assumed, some Meijin made arbitrary use of its privileges. Shusai, in the notorious ‘Game of the Century’ against the Chinese born prodigy Go Seigen, flexed his seniority to end every session after his opponent’s turn, thus allowing himself the luxury of the days until the next to consider his own move. But at least Shusai offered himself up – as indicated earlier, there were Meijin who had simply not taken on serious competitors. This high-handed wielding of the title reeks of, well, entitlement. But then, perhaps much of the position was a performance, an office – the master who does not play: that is, the master who represents playing.

In the novel, the outcome settled, much of the drama lies in the tussle of the players over the parameters of the game. Kawabata makes much of the way the length and frequency of the sessions, where they take place, how they are ended, has been carefully negotiated ‘to ensure complete equality’. A new, democratic rationalism is superseding a decorous, aristocratic order in Go, as in wider society.

In one of the few moments in which the narrator looks away from the closed, intense world of the game being played, he is shocked:

‘From the veranda outside the player’s room, which was ruled by a sort of diabolic tension, I glanced out into the garden, beaten down by the powerful summer sun, and saw a girl of the modern sort insouciantly feeding the carp. I felt as if I were looking at some freak. I could scarcely believe we belonged to the same world.’

This sounds hyerbolic, but the ‘girl of the modern sort’, the modan garu, was a movement emerging out of the 1920s and scandalising traditionalists in the way of teddy boys, rock and rollers, punks. The isolation of this reference to broader cultural developments makes it perhaps the more telling.

The narrator builds up the Invincible Meijin, the nonpareil of Go, attentive to his powers of concentration, the toll they take on his health – indulgent of the carelessness for the agreed terms that springs from these. Kawabata casts a wink at the earnestness of his novelised stand-in when he refers directly to the afore-mentioned Game of the Century, which the non-fictional Meijin, Shusai, appeared to be losing until move 160. This ingenious play turned the game and was strongly rumoured to have been devised by one of Shusai’s pupils in the Honinbo school during a recess. To the narrator, ‘such allegations were impossible to believe.’

The book’s blurb names it an elegy to the society that was usurped by the modern world. Is the elegy in part for the openness to the play of illusion that allowed there to be a Meijin at all? After Shusai, the title was never assumed by another person, rather it was attached to a major competitive tournament, up for the taking to all entrants.

No one, not even a Meijin, is really invincible – Kawabata’s loses his final game and then his life. Meritocracy has taken the place of the illusion that merely holding an office guarantees, or confers, special powers. And yet what replaces this illusion is not without its own illusions – the code of rules aiming to establish equality is slyly subverted through gamesmanship; the ruthless focus on standardised rules and competitive ranking obscures the grace and artistry that bring enjoyment to the play of the game.

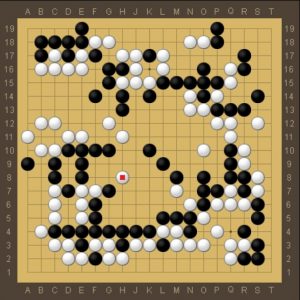

In 1997, the computer program Deep Blue beat champion of world chess, Garry Kasparov, marking the first time a computer had beaten a human at the game under tournament rules. But there was no path from this program to one that could beat a professional Go player.

Deep Blue operates largely by calculating the next possible moves, then each possible move those moves might lead to, and so on, doggedly following branches of moves through to see which are more likely to lead to a win. Though the number of possible moves in chess is huge, the number of possible moves in Go is vastly huger. We do not know how to build computers that could compute those numbers within any remotely useful time-frame.

Nevertheless, in 2016 the program AlphaGo beat the top human Go player, Lee Sedol. It did so by examining thousands of records of human games, millions of moves, and by playing against itself over and over again, until it could recognise certain moves and board positions as both more or less likely to be played, and more or less likely to win. This greatly reduces the amount of calculation it needs to do in evaluating each move.

The developers of AlphaGo then developed AlphaGo Zero, which had no human input, and after playing itself for three days was able to defeat AlphaGo a hundred games to zero. Impersonal equality before the rules of the game has triumphed over the people that invented them. The nonpareil of Go gameplay is now internal to AlphaGo and it’s descendant programs, infinite self-playing solipsisms in which ever more perfect games are played out in the utter abstract. There is not even a passing woodsman to witness.

But an elegy is not an attempt at resurrection. Kawabata respected and admired the Meijin, and all that he represents in the novel, which marks the passing with sadness. None of this entails the rejection of the emerging era, not that of Japanese modernity, nor that of our algorithmic age. His Nobel prize acceptance speech quoted the Zen saying:

‘If you meet a Buddha, kill him. If you meet a patriarch of the law, kill him.’

The disciple can only attain Enlightenment by their own efforts, and to this end must eventually part from the path of any that came before, no matter how much they are to be respected. Kawabata met a Meijin, and killed him.