2666

2666

Roberto Bolaño

2004

2008 in translation by Natasha Wimmer

This one book might have been published as five. One would have been about the incestuous sexual entanglements of a clique of European academics obsessed with a reclusive (and fictional) author with the nom de plume ‘Archimboldi’. Another about a man who may, or may not, be going mad. Another about a journalist sent over the border to cover a boxing match he knows nothing about. Another about Archimboldi’s pre-literary life as a Wehrmacht soldier.

One of the books would have been about murder. Murder upon murder.

‘..the partially charred body of Silvana Pérez Arjona was found in a vacant lot. She was fifteen…’

‘Maria de la Luz Romero died … She had been raped and hit multiple times in the face … The cause of death was stab wounds to the torso and neck, which had pierced both lungs and multiple arteries.’

‘According to the medical examiner, she had been beaten and whipped: the marks of a wide belt were still visible on her back.’

‘Her vulva and thighs showed clear signs of bites and tears, as if a street dog had gnawed at her.’

There are characters in this book. There is narrative of sorts. Above all there are murders of women, dozens and dozens of bodies, many unknown, many sexually violated, tortured, the scant details of their identities and deaths submitted with forensic professionalism.

Though Bolaño did toy with the idea of allowing each part of this book to be its own book, it, or they, were constructed as an organic unit. How are they bound together?

Coincidence is a Luxury

Guiseppe Arcimboldo painted canvases teeming with objects, riddled with double meaning and allusion. He delighted the royal courts of sixteenth century Europe with teasing creations that often seem a simple collection of stuff, only to reveal, from the right angle, a hidden unity. Take The Gardener:

Oh, ok, I’ll give you a clue: turn it upside down.

The narrative non-sequiturs of Bolaño’s 2666 don’t initially appear to add up to a whole story, but it is impossible not to infer a relationship between each section, and this leads uneasily to thought of the section, The Part About The Crimes. And to the thought that it is of a part with the rest.

The horror of the crimes seems incomprehensible, alien, but perhaps this is only because we look too closely, failing to pull back and take it all in, to see that they are all too easily linked to our own lives. On the other hand, pulling back shows us the deaths not in their unique horror, but as just another part – something that can be ignored in itself – of the overall picture. Once you see the gardener, his component parts lose their individuality, and matter not for themselves, but only as they were chosen to illustrate the man.

The book contains a fictional painter, Edwin Johns, famous for ‘an ellipsis of self-portraits … seven feet by three and a half feet, in the centre of which hung the painter’s mummified right hand.’ Johns says that: ‘Coincidence … is like the manifestation of God at every moment on our planet. A senseless God making senseless gestures at his senseless creatures.’ The fragmentary nature of the book might seem to endorse this nihilism, the nod to Arcimboldo’s painting a suggestion that any pattern made out is an illusion indulged in by the viewer.

If this was the case, the book would be a senseless parody of a senseless universe. But this is belied by Bolaño’s long effort to produce the thing – he had written thousands of pages by 1995, and the book was not quite finished when he died in 2003. It is belied most of all by the memorial litany of murdered women, the implacable horror of which cannot be conceived as parodic. No doubt, though, the senseless is explored here. Bolaño exhibits a dark night of the soul, the unquenchable search for meaning that remains, apparently senselessly, even in the face of despair.

Edwin Johns also speaks of a friend who believes ‘in order, in the order of painting and the order of words, since words are what we paint with.’ This friend believes that there is no ‘coincidence for the person who gets up at six in the morning , exhausted, to go to work: for the person who has no choice but to get up and pile more suffering on the suffering he’s already accumulated’. For this friend, coincidence is a luxury.

In a whispered revelation Johns tells that the meaning behind the finishing touch to his last work – the cutting off of his painting hand – was the money it would make. Beyond the obvious symbolism of avarice as the death of creativity, integrity, self-restraint, there is in this ugly self-mutilation at the heart of an acclaimed and astronomically expensive artwork a resonance with the book’s broader themes.

In The Part About the Critics, European academics – art lovers, humanists – travel from conference to conference, country to country, debating the meaning of books, the meaning of life. One day, drunk and gnawing on jealousy, two of them beat a man almost to death, an experience that imparts a sexual charge and profound guilt. They talk of the event as ‘the thing that can’t be explained’ and worry over what it says about who they truly are. With time the guilt passes, life goes on.

In The Part About the Crimes, the women of Santa Teresa die, women working in and around slums rapidly propped up against the factories of the de-regulated border zones of Mexico. These are a consequence of the North American Free Trade Agreement, which led to a collapse in Mexican farming, subsequent large movements of people, and the upheaval of their economic and social status. For these people, too often, violence means that life does not go on.

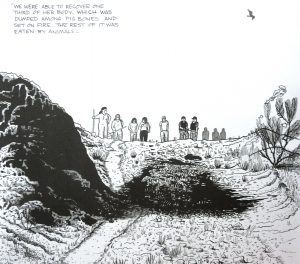

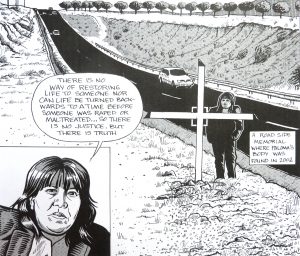

Bolaño points to the parts of our globalised world and invites us to join the dots. Because the Crimes are real, more or less. Bolaño has fictionalised the Ciudad Juárez femicides. Rubi Marisol Frayre, whose fate is illustrated towards the beginning of this article, really was murdered.

I would be fascinated to know what those unaware of this make of the book – the experience of reading 2666 without knowing that things very much like those it describes have happened, and continue to happen, is closed to me. ‘Who,’ I imagine the hypothetically unaware reader thinking, ‘is murdering all these women? Why does the author so monotonously describe their deaths? What does it have to do with the story?’

Perhaps the question invited by Bolaño is: ‘What does it have to do with me?’ When we see the whole of something – say, the modern world – we can, in starry-eyed admiration, ignore any ugly parts. When we see the parts, we can feel bad about the ugly while ignoring the connection to the beautiful.

Unless you’re a woman in Ciudad Juárez, looking over your shoulder in the dark on the long walk home from the late shift at the factory, knowing that the flow of money and drugs over the border means that the criminals can pay off the police, that the police are often criminal, that your life is cheap. Coincidence is a luxury.

Bought by Blood

Bolaño is in the place of Ivan Karamazov, unwilling to allow violence to be accommodated and explained, to be the spice of life, to allow evil as the yeast that raises the bread of life. Dostoevsky’s character says, in relation to the suffering required for the attainment of Christian salvation:

I decline the offer of eternal harmony altogether. It is not worth one single small tear of even one tortured little child that beat its breast with its little fist and prayed in its foul smelling dog-hole with its unredeemed tears … by what means will you redeem them? … Will you really do it by avenging them? But what use is vengeance to me, what use to me is hell for torturers, what can hell put right again, when those children have been tortured to death?

Ivan goes on to ask, if we were given the task of building a world that would culminate in happiness for all, would we agree to build it on a foundation of suffering, of the suffering of even one child:

…are you able to allow the idea that the people … would themselves agree to accept their happiness being bought by the unwarranted blood of a small, tortured child and, having accepted it, remain happy for ever?

Bolaño shows us that much of at least our earthly happiness is bought at this very price, over and over again. The Crimes, the murders of women, are to the aspirational citizens of a globalised world what Edwin Johns’ mummified hand is to his self-portrait, what the torture of a child is to the glory of heaven.

The number 2666 is not explained, or even alluded to, anywhere in the book it titles. But in another novel entirely, Amulet, Bolaño writes of:

a cemetery in the year 2666, a forgotten cemetery under the eyelid of a corpse or an unborn child, bathed in the dispassionate fluids of an eye that tried so hard to forget one particular thing that it ended up forgetting everything else.

Presumably it is this forgetting that Bolaño wishes to fight by presenting so nakedly the many murders. To do so by bringing to mind something very close to, but in the end not, the truth, is a strangeness. We are admonished to remember via a misremembering.

This invites an interrogation of memory. After all, our memories of someone who is gone are an abstraction of them, a representation of them. They are not a photographic record, their elements burned into a fixed pattern at the moment they occur. They are reconstructed by drawing together the disparate fragments we have as evidence of them in our minds, including our memory of previous rememberings.

As a result, each time we remember someone, we blur their image at the edges, mixing them gradually in with our other memories, and with ourselves. In this way, each act of memory distances us from the person remembered in the same moment it connects us to them.

In the long term – think generationally – memories can of course only be vague, and will eventually become legendary. Yet even when the details have become partly fictional, when dates, or even names, are forgotten, these traces are still testament, however obscurely, to a human life.

No one can expect their name to be remembered in a thousand years’ time, but if we image a life as a pebble dropped into the pond of the universe, we know that the ripples created will wash right through it. An act of memory is an amplification of the ripple. The wave of deaths in Ciudad Juárez has washed through Bolaño in the form of this book.

All things considered, there can be no doubt that he intended his fictional crimes to remind us of the real. He was rigorous in his research on femicide in Ciudad Juárez, working closely over many years with Sergio González Rodríguez, the brave journalist who did the most to bring those crimes to the attention of the wider world – and who appears, lightly disguised, in 2666. There is some suggestion too, that Archimboldi’s first published novel is plagiarised from the journals of a Russian Jew murdered by the Nazis. Perhaps, and this may be a stretch, this is a hint of the discomfort attendant on Bolaño’s own appropriation of real life tragedy.

A Terrible Heroism

Despite the size of this book there are some things Bolaño did not include, perhaps so as not to compromise the picture of human evil, to not let us off the hook. In Ciudad Juárez there is also a terrible heroism. Despite the impunity of the drug cartels, the corruption of the police, and the lawlessness that grows in their shadow, there are those among the most vulnerable, among the women themselves, who are unbowed.

Their work is chronicled in La Lucha: The Story of Lucha Castro and Human Rights in Mexico, a documentary graphic novel drawn and written by Jon Sack. Lucha successfully ran, and minded, her own business. But something called her to remember:

…every day the belief grew stronger in me that I could not be part of inhumane structures that offered me a more-or-less comfortable living, as long as I forgot about those who were suffering.

In response, Lucha founded, and until recently ran, the Centre for Human Rights for Women, which provides emotional, practical and legal support to women, and families of women, who have been victims of gender-related crime. She sees that work as a memorialisation, something she describes by remembering the words of her murdered friend, Bety Cariño:

We denounce human rights violations so that we do not forget, to preserve historical memory in the heads and hearts of the torturers who burn down our houses, threaten us, rape, disappear and murder our children.

Saúl Reyes Salazar’s family campaigned for environmental and human rights in the Juárez valley. Six members of the family have been murdered, and Saúl sought asylum in the USA. He has said:

I believe that for all these dead there will never be justice … No one will be detained … No one jailed … No one condemned … But some day I’ll go back and erect a great monument that says in waging war, Calderon supported the deaths of all these people. And all the names will be there … So the memory of those who died stays with us forever because these were human lives.

2666 could be considered a great monument erected to the memory of those who have died in Ciudad Juárez – but how could this be so if it names them by fictional names? Through the character of Archimboldi, Bolaño ties the crimes of the disguised city to the great crime of the Holocaust, and in doing so suggests that his book takes aim at all crimes. By only alluding to real injustices, perhaps he prompts the reader to the work of uncovering them. Rather than a monument, 2666 may be an invitation to make our own contribution to the continuous, monumental work of bearing witness to evil.