The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini

1558

1956 in translation by George Bull

‘…I noticed someone riding along the edge of trench on a mule … I was well prepared before he came opposite my line of fire, took accurate aim, and hit him … right in the face … The man I hit was the Prince of Orange.’

So this Benvenuto was a famous soldier then, I hear you ask. No, but he was one of those people who, if they do anything, are very good, the best; tremendous – everyone says so (we’re not talking about that Prince of Orange, keep up). He intended to tell his story ‘with a certain amount of pride.’

In 1527, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, was Emperor of many things, but not, for some reason, Rome. His army, happening to be in the neighbourhood, decided to change that, and as the city had no significant standing army at the time, the residents, including Cellini, took up arms to defend their homes. Hardly had his arms been taken up, than on a brief expedition to the walls, intending to observe the progress of the fighting, he had a potshot at a figure who stood out from the rest of the attackers. And, so he relates, killed the commander of the enemy army, the Constable of Bourbon.

Then, inspired by:

‘an accompaniment of blessings and cheers from a number of cardinals and noblemen … I forced myself to try and do the impossible. Anyhow, all I need say is that it was through me that the castle was saved that morning’.

Despite having nothing to do with his career, these snippets give an excellent picture of the general tone of Cellini’s autobiography, which is despite – or because of – his overweening self-regard, the sort of read that gets paired with the otherwise redundant word ‘rollicking’. It’s a real-life picaresque, abounding in colourful events. Cellini whisks us through a gallery of historically momentous people, places: Popes, Medicis, Titian, Michelangelo, the court of Francis of Angouleme. The exploits above were during the Sack of Rome:

‘Night came on, and the enemy were in Rome. Those of us in the castle, especially I myself with my constant delight in seeing unfamiliar things, stayed where we were, contemplating the conflagration and the unbelievable spectacle before our eyes.’

All of this, though, is merely the backdrop to the improbable life of the author, who immediately goes on to say of this unbelievable spectacle:

‘But I shall not begin describing it; I shall just carry on with the story of my own life and the events that really belong to it.’

And he does ‘just carry on’, without chapters or transitions, in relentlessly conversational fashion. Indeed, the book was dictated, after an abortive attempt by Cellini to write it himself – an attempt he dismisses in the unpromising first sentence as too time-consuming and ‘having seemed utterly pointless.’ Chattering away to a servant as he worked, you can think of this as a prototype podcast, only with all episodes delivered en bloc.

Instead of the whimsical anecdotes of middle-class comedy-nerds though, the story of this life is driven by Cellini’s hair-trigger temper and Viking warrior levels of pique. He frequently complains that his misfortunes are due to the hate of his venal enemies. But the frequency with which he falls out with people becomes somewhat suspicious.

As a young Florentine Cellini got into a row with rival goldsmiths and was fined for assault by the magistrates. Boiling with anger at what he saw as the injustice of the sentence, he went after the man he had struck and attempted to stab him. Fleeing the consequences was what took him to Rome, where his skill as a craftsman brought him to the attention of a bishop, and then the Pope.

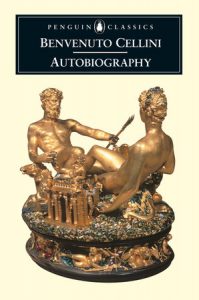

This really ought to be the meat of the book: the work of a great artist, courted by Dukes and Kings; the innovative technical solutions; the inner search for inspiration. And there is some of this. Cellini writes at length about the gestation of the Saliera, which graces the cover of this edition of his book and has been valued at £35 million. More bling than Mr T, this is a salt and pepper cellar. A minor part of a dinner service. Executed with great skill, it is nevertheless testament to the timeless truth that some people have more money than taste. It was scandalously stolen in 2003, when by happy coincidence scaffolding was erected against a Vienna museum shortly before a man who ran a security alarm firm took a tour of the exhibits. He put two and two together. Thankfully, the Saliera was recovered three years later.

It’s been said that Cellini is better known for his book than his art. And even tyrants have limits. Eleanor of Toledo, Duchess of Florence, had him design a jewellery piece for a valuable diamond of hers. She later had it reset because it was thought it ‘would make a better show if it were set less elaborately.’ It may be that this is why Cellini doesn’t appear in Giorgio Vasari’s famous chronicle of Renaissance notables, The Lives of the Artists, though it features many of his contemporaries. Another reason might be the bitter enmity of the two – Cellini’s autobiography contains a passage in which he humiliates Vasari in the belief that the painter had spread a malicious rumour about him.

Still, he did also produce, for Cosimo I, Duke of Florence, a statue of Perseus that is a remarkable work of art by any standards. Bronzes of such size had only been cast in sections before but Cellini wanted to do it more or less in one go (‘…what you want done is beyond the powers of art. It’s simply impossible’, said one of his staff. Allegedly.). Its creation provides one of the few pieces of drama in his story solely to do with the artistic process.

The specially built furnace was brought to such a pitch of heat that the roof of the workshop caught fire. As time came to pour the metal, Cellini was taken so fiercely with a fever that he thought, never a man to under-employ hyperbole, he ‘would certainly be dead by the next day.’ Despite his instructions, the men let the alloy curdle – so he leapt from his deathbed to pile wood on the fire until ‘there was a sudden explosion and a tremendous flash of fire, as if a thunderbolt had been hurled in our midst.’ The cover of the furnace itself had cracked open, but rushing to plug it, he was able to complete the cast.

The Perseus was an immediate success, holding out the head of the gorgon to the three existing statues on the Piazza della Signoria, which, carved out of stone, were made to seem appropriately petrified. The sinister undertone is that the earlier works, made to celebrate Florence as a republic, have been silenced by commission of a tyrant. Some years earlier, censured by fellow Florentines for supporting the Medicis, Cellini responded:

‘You idiotic fools, I’m a poor goldsmith, and I work for anyone who pays me, and there you are jeering at me as if I were a political leader.’

To repeat, paying attention to anything beyond his own affairs wasn’t his style. Instead of the republican uprisings, wars and intrigues of the time, what astounds and interests are the incidents that develop from his dangerously flamboyant, emotionally incontinent, utterly self-obsessed approach to life.

There was that time he was imprisoned for various murders and the theft of precious stones (self-defence and trumped up charges, says he), then escaped from the tower – having removed the nails from his cell door one by one and camouflaging his progress with wax replicas – by shinning down tied-together bed-sheets; was then recaptured and slung in a dungeon in which his nails grew ‘so long that I could not touch myself without their wounding me’, but where he received visions of Christ and was ‘full of great rejoicing’, so that ever after ‘a light – a brilliant splendour – has rested above my head, and has been clearly seen by those very few men I have wanted to show it to.’

On the other hand, there was the court case in Paris, which seemed to be going against him, so to defend himself from ‘the leading spirit in that unjust lawsuit’ he had no other option than his ‘large dagger.’

‘One night I stabbed him so many times in the legs and arms (taking care, however, not to kill him) that I deprived him of the use of both his legs. Then I went after the fellow who had brought the suit, and notched him so effectively that he abandoned it.’

It’s possible that the heavenly light shining above Cellini’s head was not apparent to these men.

Or how about the time he made friends with a necromancer and they staged a ritual in the Coliseum to persuade the powers of hell to reunite him with his lover. The virgin boy brought as medium saw legions of demons, and fire rushing at them, and ‘then he clapped his hands over his eyes, and started crying that he was dead and didn’t want to see any more.’ The lot of them shaking in fear, Cellini called on a companion to burn some stinking herbs to drive away the devils:

‘The instant he made a move, Agnolo blew off and shat himself so hard that it was more effective than the asafoetida.’

This last escapade invites the thought that the whole book could be a lark, the self-mythologising of a teller of tall tales in the vein of Woody Guthrie’s riotous autobiography Bound For Glory. But where Woody wrote for the sake of the story, and with a gleefully ironic eye on his own legend, Cellini is too obviously keen to self-justify, settle scores, and establish status.

‘Lark’ doesn’t fit the callous maiming of his legal opponents. He could be a viciously violent man, and his sexual involvement with models and servants, male and female and some very young, would provoke #metoo in our time, if not prosecution. But one can read with an ironic eye on Cellini’s attempts to puff himself up, and so, while he doesn’t come across as likeable in any more than short doses, it’s easy to be marvelously entertained by the story of his life.