Hrafnkel’s Saga and Other Stories

Unknown authors

Circa 13th Century

1971 in translation by Hermann Pálsson

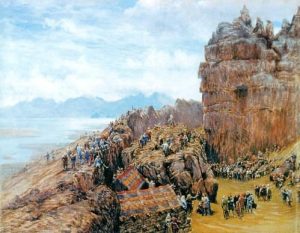

Iceland was minding its own business until around 870 AD, when, finally, humans decided to try living on it permanently. These Nordic pioneers had travelled west to an island wild with volcanic activity and afflicted by punishing cold. Unruled and unruly, they were accustomed to claim summary justice, by the sword if necessary, according to a Germanic moral code characterised by the fierce guarding of honour.

Having more than one dimension, they nevertheless realised the value of civil infrastructure, and in 930 established perhaps the earliest example of a national parliament: the Althing. In Old English, and related languages, a ‘thing’ was a meeting or assembly – a council gathered to discuss some important matter – before it took on the connotation of any matter at all. That use survives in our word ‘hustings‘, or ‘house thing’; originally a gathering at the leader’s homestead to hear speeches. In mediaeval Iceland, Patriarchs vied for followers across 39 districts. Those with the most influence spoke for their district at the annual Althing, where laws were made and claims were judged.

In that auspicious year 1000 AD, the Althing declared Christianity the official religion of Iceland. Under the auspices of the new clerical administration, a more literary and humanistic culture developed, and out of this the Icelandic Sagas were produced. Much of their drama is born out of a clash between ethics: on the one hand, the honour-based imperative of personal prestige, according to which not an iota of dignity may be ceded; on the other, the understanding that a stable society requires give and take between neighbours and that turning the other cheek to a rigid code might sometimes yield preferable results.

And it’s true that the message of these stories is something less savage than we might imagine for the period. Take Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned, a 2009 short story by Wells Tower. By describing a perfunctory but brutal Viking raid in contemporary US vernacular he creates a thinly veiled allegory (though I didn’t notice it on my first read…) for the stupid destruction wreaked by our present puffed-up superpower.

Like Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned, the Sagas are historical fiction, written in the thirteenth century but set in the tenth, well within the Viking heyday. The Christian authors are rather more generous to their pagan forebears than is Tower. The title character of Ivar’s Story was an Icelander who did actually become Court Poet to the Norwegian King. The saga, though, is an invention. It recounts the poet’s grief when his brother marries the woman he loves. King Eystein offers wives, lands, money to soothe his friend, but Ivar has no heart for any of these. At a loss, the King offers the only remaining thing he can think of:

‘Come to me every day before the tables are cleared, when I’m not engaged in matters of state, and I shall talk with you. We’ll talk about this woman to your heart’s content for as long as you wish, and I’ll devote my time to it. Sometimes a man’s grief is soothed when he can talk about his problems.’

A contemporary writer putting these words in the mouth of a tenth, or even thirteenth, century character might well be accused of the anachronistic insertion of present preoccupations with talking therapies and men in touch with their feminine side.

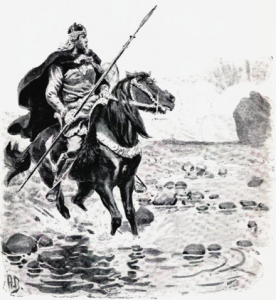

The title story of the collection throws us back on our Viking stereotypes though. Hrafnkel (this guy seems to know how to say it) loves his horse. So much so that he dedicates her to his god, Frey, and swears a sacred oath to kill anyone else who rides her. Then he hires Einar to herd his sheep, and explains at length how many other horses Einar is welcome to ride. I won’t draw the diagram.

After Hrafnkel tugs his axe out of Einar’s face he’s sued for damages by the lad’s family. Mediaeval Icelanders lived by the motto: ‘Where there’s blame there’s a claim’. He loses his lands and goods in the case, not to mention being tortured, and decides that sacred oaths have a lot to answer for. Accordingly, he gives up religion and works hard until he makes his fortune over again. Years later Eyvind Bjarnason, a powerful relative of Einar’s family returns from long travels abroad. Hrafnkel has known all along that this chieftain could protect his enemies and seizes the chance to kill him, then takes back by force everything he had forfeited.

Modern commentators have found it difficult to identify with the ethical framework of this saga, leading some to suggest that ‘Hrafnkell turns out to be a total asshole.’ With his killing of innocents at the beginning and end of the tale, can Hrafnkel be considered its hero? R.D. Fulk’s persuasive analysis argues that he is, because he changes from an ideologue to a pragmatist.

Hrafnkel doesn’t actually want to kill Einar, but he feels bound by his oath: ‘I’d have forgiven this single offence … but my faith tells me that nothing good can happen to people who break their solemn vows.’ When nothing good happens to him anyway, he thinks better of holding his honour in such high regard. After being shamefully tortured he chooses, over a heroic death, to live with his humiliation for the sake of his sons.

Hrafnkel isn’t particularly keen to kill Eyvind either, but one of his feudal servants harangues him for his disgraceful cowardice in ignoring the chance for revenge. He deplores her motives, but agrees to the act because, according to Fulk, he reasons that otherwise his household will lose respect for him and will fall into disarray. At the close, though he has them in his power, Hrafnkel is more lenient to his enemies than they were to him, passing up the chance to torture, kill or impoverish them in return.

While this might acquit Hrafnkel of the charge of being a total asshole, it doesn’t seem quite enough to make him utterly un-asshole-ish. It would have been possible for Hrafnkel, like a jaded film cop nearing retirement, to have uttered the immortal lines ‘I’m too old for this shit‘, and to have gone off to his allotment leaving his kinfolk to their bloodthirsty honour-killings – and Eyvind alive.

But it’s also true that in rejecting the heroic ideals of earlier writing, in which honour, purity and victory, were lauded, the authors of the sagas were contributing to the long emergence of a realist literature out of epic, mythic roots. To get from paragons like Achilles, Roland or Galahad to the flawed, or even anti-heroes of Dostoevsky, Hamsun or Camus, we needed plenty of Hrafnkels in between.