The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins

The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing

2015

Humanity as a virus is a popular metaphor of secular apocalypse. We are parasites stealing life from Mother Earth and selfishly ruining her capacity to nurture the finely balanced and mutually supportive dance of the innocent plants and animals. Gaia may be about to annihilate us with her immune system: climate change the rising temperature of a world-wide fever that will consume us and allow the patient to recover.

But what’s wrong with viruses? The metaphor only works because a virus is something that we dislike. From the point of view of a virus, what viruses do may seem perfectly reasonable, perhaps even virtuous. If we were to finally wipe them out with our hygiene and inoculations would that not be another example of our evil, virus-like, eco-cidal behaviour? Does Gaia hate viruses, or are we their only enemies?

The ease with which we see ourselves as viruses comes from our idea of ourselves as apart from, rather than a part of, nature. We think of the natural world as something over there, outside our homes and cities. There are ‘natural’ ecosystems and habitats which our presence destroys and to allow them to flourish we need to leave them alone. Taking our own prejudices out of the picture leaves us one more organism among others, naturally doing the things we do given our nature.

The Matsutake Mushroom

In Japan, as in many parts of our twenty-first century world, volunteers are working to conserve and restore the woodlands they remember from their youth and that have vanished as the country became urbanised. Paradoxically, they are doing so by clearing and managing the apparent wilderness that has grown up since the people left their peasant lifestyles behind. In the abandoned forests, an invasive Chinese strain of bamboo shades young pine trees, which struggle to survive. Are the pine trees being naturally out-competed? Or are they being artificially killed because humans brought non-native Moso bamboo to the Japanese islands?

The community groups restoring Satoyama, or traditional peasant woodland, draw no such distinctions. Peasant farmers once irrigated the land to create rice paddies: frogs and dragonflies flourished. They coppiced oak trees for firewood, the stumps growing new limbs again and again: Japanese Emperors fluttered the air, gluttons of the young oak sap. They scoured the forest floor and used the organic matter collected to fertilise their crops: in the thinned soil, hardy pine trees gained a foothold. And in the roots of the pine trees, mushrooms grew.

Human cultivation is yet to produce a matsutake mushroom: they will only grow entangled with ‘the plants, slopes, soils, light, bacteria, and other fungi’ that make up their homes. Satoyama is neither nature in the raw (whatever that might be), nor intensive agriculture. It is a landscape that forms out of the entwined lives of many organisms, where people are one element in a developing ecosystem. In her book, Tsing makes the matsutake mushroom an emblem of such mutual life-worlds.

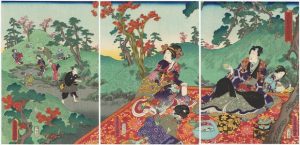

The Japanese festivals of cherry blossom viewing are well known, but the autumnal equivalent of gifting matsutake has largely passed the rest of the world by. The mushroom has been a poetic symbol of the melancholy Fall season for hundreds of years and to a Japanese nose ‘smells like village life and a childhood visiting grandparents and chasing dragonflies.’ As the Satoyama woodland disappeared, so did the mushroom, and Japanese demand drove a globalised matsutake market. Prices fluctuate according to harvests, but at the time of writing a kilo could easily set you back £500.

Like many fungi, matsutake grows in symbiosis with plants. The main body of a fungus is a potentially vast network of filaments lying below the soil, from time to time fruiting the mushrooms that poke their way toward the surface. These filaments can thread themselves into the roots of trees, connecting forests together in a wood wide web. Recent science has shown how, by means of these prosthetic roots, healthy adult trees can nurture shaded saplings by sharing nutrients, or if attacked by pests can warn their neighbours to prepare to repel boarders. Matsutake likes to live with pine trees.

Pines are pioneers. In partnership with their fungi they can live in exposed and impoverished locations. Hence they often live on the fringes, such as high up where soil is scarce, and thrive in disturbed landscapes. ‘When a volcano erupts, or a glacier moves back, or the wind and sea pile sand, pines may be among the first’ trees to spring up. Forests first logged indiscriminately, then managed as monocultures, then abandoned as the local timber trade is undercut by exploitation elsewhere, are an example of the Capitalist Ruins of the book’s title. In them, pines take over.

But this is an ecology in motion: pine trees and their fungal symbiotes, such as matsutake, always arrive together on, say, the barren rock a glacier has retreated from. The matsutake eats the rock, passing the valuable minerals, in now digestible form, to the pines. As the rock is broken down it becomes soil. The soil banks up and becomes fertile for broadleaf trees that as they mature shade out the pines. The next generation of pines plant their roots beyond, chasing the diminishing glacier, the whole forest advancing along the stony ground. Or they may not survive, and new pine growth will have to wait until the woods are disturbed again, by fire perhaps. Or logging.

Tsing points out the dynamic nature of these habitats to show us that our fellow creatures have histories too. Sustainable forests are human creations and require human action – as in Satoyama – to be arrested at one point in their development and kept static. This point, of course, is the one at which humans can extract something valuable.

De-historied Lives

Humans often isolate one product of an environment and exploit it over and over again. But this, in reality, means isolating it from its history as part of an evolving ecology. To make sure that we can log a consistent quality and amount of timber we manage the landscape so that competitor species are suppressed and carriers of diseases and parasites are wiped out. The trees themselves are not allowed to fully mature but are chopped down while still young. In this way pine plantations are maintained and their relationship with the broadleaf trees they prepare the way for is refused.

Tsing argues that capitalism proceeds by tearing objects out of their networks of relationships and pretending that, instead of these, they are constituted by some ahistorical essence. So, for instance, the regiments of trees managed for harvest that deny the vaster cycles of forest movement across the landscape in favour of the isolated life-cycle of the timber producing pine.

This approach goes back to the birth of capitalism and two of its exemplary commodities. First, sugarcane:

‘All the plants were clones, and Europeans had no knowledge of how to breed this New Guinea cultigen. The interchangeability of planting stock, undisturbed by reproduction, was a characteristic of European cane … which had no history of either companion species or disease relations in the New World. As plants go, it was comparatively self-contained, oblivious to encounter.’

Second, slaves:

‘As cane workers in the New World, enslaved Africans had great advantages from growers’ perspectives: they had no local social relations and thus no established routes for escape … They were on their way to becoming self-contained, and thus standardisable as abstract labour.

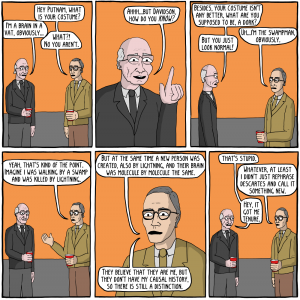

How far it’s possible to abstract a human being from their environment has been examined via a thought experiment by the philosopher Donald Davidson:

‘Suppose lightning strikes a dead tree in a swamp; I am standing nearby. My body is reduced to its elements, while entirely by coincidence (and out of different molecules) the tree is turned into my physical replica. My replica, Swampman, moves exactly as I did according to its nature, it departs the swamp, encounters and seems to recognise my friends, and appears to return their greetings in English. It moves into my house and seems to write articles on radical interpretation. No one can tell the difference.’

Davidson purposed to show that Swampman would not be an identical replica of his – because lacking the historical basis of the unfortunately vapourised philosopher, the creature’s words and thoughts could not refer to what they appeared to be about. When it greeted a ‘friend’ it would in fact be mechanically responding to a stranger. It’s words would have no meaning. Perhaps it couldn’t be said to have thoughts at all.

Philosophers have long argued whether it’s possible that there could be creatures physically identical to humans but lacking a sense of self (Swampman’s a favourite, but they also love zombies). They argue because we often imagine ourselves as a mind and a body, potentially separate items, much as we used to imagine ourselves as a soul and a body. This is also what gives us notions like brains in vats, and minds abstracted from bodies and ‘uploaded’ into the internet.

These ideas can have pernicious consequences. The anthropologist David Graeber discusses slavery in his book Debt: The First 5,000 Years, arguing that we consider ourselves ‘as masters of our freedoms, or as owners of our very selves. It is the only way we can imagine ourselves as completely isolated beings.’

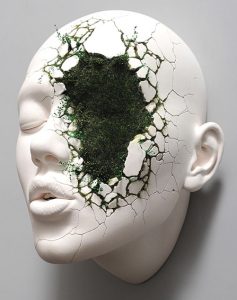

By paying attention to the unpredictable mutuality of human-matsutake assemblages, Tsing means to help us escape our isolation. By mingling with the things of the world, by noticing how we act and react to them, we may avoid what Graeber calls the ‘essential horror of slavery: the fact that it’s a kind of living death.’ The organic products of capitalism are in this sense undead, zombified – existing as commodities, cut off from the social worlds in which they had a history and instead reproduced identically, eternally.

The separation of mind and body is a dream of the halting of history, of immortality: the body may decay and die, but the mind can leave it behind. The price of the dream is that the mind must control the body as its slave. We discipline our physical lives in order to optimise our dream lives and end up disciplining our dreams too. We struggle for the same off-the-shelf successes once symbolised as house-car-picket-fence, now offered by the economy of (ersatz) experience: Machu Picchu, self-curated streaming services, street food.

Politics from the Fungal Perspective

Tsing wants us to look out for the serendipitous emergence of mutual benefit – such as matsutake foraging – in places that we are, rather than that we own. Instead of trying to master our environment we ought to be within it, alive to its rhythms, one more thread of the universe’s weave, no more, no less. In this there’s the taste of Taoism, Zen practice – but also of the networked world of the internet. Like the pervasive threads of fungal mycelium, the cloud of our virtual interactions dissolves the boundaries between things and precipitates spontaneous uprisings as people discover their good in each other, the Arab Spring perhaps the paradigm example.

Not, however, necessarily an example Tsing would cite. For her, Progress, the desire to master the world, is the totalitarian ethos that has left the world in ruins and needs to be abandoned:

‘…the world will not be “saved”. … If we don’t believe in a global revolutionary future, we must live (as we in fact always had to) in the present’.

Hold on, though, because metaphors of entangled networks and encouragements to live on our wits, entrepreneurs of our selves, are the stock in trade of today’s capitalism too. The captains of industry would be quite happy for the rest of us to make do and mend among the ruins they have left. To do so seems a form of quietism. The risk is that by opening ourselves to the lessons of the non-human environment, we close ourselves off to the social groupings that have traditionally resisted capitalism: political parties, trade unions, pressure groups, and so on.

Eschewing Progress seems to effectively give up on countering the destructive status quo, even to ignore its imminent threat to our own lives. As a critic of this book has it:

Tsing takes that critique on the chin in her article Is There a Progressive Politics After Progress?, well aware that what she has put forward ‘is hardly a robust political program.’ She is, though, a seasoned activist who has by no means given up the struggle. What she has given up is a mode of struggle: the ‘clash of swords’ that pits ultimate visions of the future against each other, where either capitalism is The End of History, or it must be opposed from ‘within a universal politics of resistance’.

Seeing these ideological wars as, like the real thing, so far producing only ruins, she prefers to stand aside from the battle, to look around her. Away from the noise of human squabbling she hopes to learn, from the creative adaptations of our myriad neighbours, ways of being that allow progress on immediate practical matters and leave the universe as a whole to itself.

Abandoning the desire to master – and therefore enslave – might lead us away from the sound and fury of political and economic utopias that threaten to bring the End of the World (with added mushrooms). Living in the present might lead us back to ourselves, reconciling our minds with their immediate natural environment – our bodies.

Living in the future, though, may be the natural thing for humans to do. When we say that humanity is a virus, we imagine a virus only as something that viciously attacks humans, and the metaphor damns us. If, with Tsing, we cease to see humans as the apex of ecosystems, we can recognise that humans and viruses flourish together, their numbers in dynamic balance – and that, maybe, there is room for humans too, and their visions of worlds to come.

What’s advocated in this book is to let go the need to save the world all at once by clearing the intellectual undergrowth to allow this or that grand theory to grow unchecked; and instead to forage among whatever humble dreams of near-futures sprout out of the run-down, unregulated hinterlands of thought. The hope is that these cross-pollinated mongrels are the survivors that will thrive amid the ruins of Progress.