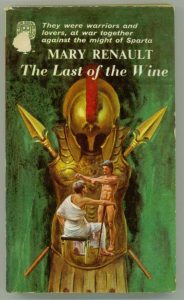

The Last of the Wine

Mary Renault

1956

A very heaven, or perhaps Olympus, for Classics nerds, this story is set in late fifth century BC Athens and comes well stocked with its truly legendary citizens: Xenophon, Aristophanes, Alcibiades, Plato, Socrates.

At its heart is the love of Alexias and Lysis, two of the circle of young men fired by the wisdom of Socrates (Renault spells his name ‘Sokrates’. I don’t know why, but it lends a pleasing air of academic nicety). Many members of this circle are recognisable from the dialogues of Plato, as is the homoerotic relationship our lovers form. It is a real and deep love, though at times one could mistake it for Platonic in the modern sense.

In all this time, Lysis never asked anything from me besides a kiss. I understood him, that he wanted me to know he was in love from the soul, and not, as they say, with the love of the Agora.

Even when the passion picks up, it’s never less than tasteful, as in this lyrical, if a little mannered, passage:

I lay between sea and sky, stricken by the hunter; the fiery immortal hounds of Eros, slipped from the leash, dragged at my throat and at my vitals, to bring the quarry in.

To cap it all, Lysis is the name of a boy in Plato’s dialogue of the same name, with whom Socrates teasingly explores… the nature of friendship.

Whether to Speak the Names of Love

Mary Renault wrote frequently of love between men (and on occasion women) at a time when to engage in a male homosexual act was to commit a criminal offence under UK law. Perhaps as a result, her novels present a restrained and idealised homosexual love and might be criticised for pandering to the ‘as long as they don’t throw it in my face’ brigade.

Her approach is to look for what is universal in love, whether between man and woman, man and man, or whomsoever, and her characters take pride in their love, not their homosexuality. She apparently did not look favourably on the gay pride movement. Gay pride, of course, foregrounds particular forms and expressions of love, in answer to their superstitious repression.

To see the contrast as an antagonism, as some will, including it seems Renault herself, is a shame. There’s no reason why these approaches can’t be complementary. To emphasise now similarity, now difference, is to move toward a comprehensive view. The championing of what is particular to homosexual love (not to mention the full panoply of loves that exist beside the heterosexual) can quite easily sit alongside the recognition of what is common to all loves. What is this but the play of the eternal Platonic Forms with their infinitely varied instantiations?

And the way Renault presents gay love so straightforwardly, eschewing any direct political commentary, her political act being the simple fact of presentation, is in its own way bold. What, anyway, is so remarkable about homosexuality? It’s been going on these thousands of years. While there may be problematic elements in her work, she is still remembered fondly by many gay men who came of age in the mid-twentieth century English speaking world.

Character Flaws: Ancient vs. Modern

Still, the touch of reticence in her treatment of this theme is of a piece with a niggling sense that, while this book is very engaging, there is also something about it that I find strangely arms length. Brutality and degradation are depicted, particularly when the Spartans lay siege to Athens and hunger lays waste to its inhabitants, physically and morally. Her characters do suffer, do make mistakes, do battle to overcome themselves.

But we see that their intentions are always noble, though the flesh is sometimes weak. It is, from beginning to end, clear who is good and who is evil. Good and evil is by no means restricted to one or other faction, but all characters fall into one or other category.

In this it is reminiscent of Star Trek: The Next Generation, that utopian vision of the USA. The programme was cast so far in the future that I could suspend disbelief and accept its idealism in a way that I could not with, for instance, The West Wing.

The result is that there is little moral jeopardy. The characters that we care about are incorruptible, after their model Socrates, and can at worst suffer and die nobly in defence of the good. When Alexias faces a crisis, it is over a desire still more chaste than that he shares with Lysis.

One might argue, albeit ironically, that they could be considered authentically ancient characters. Theories of the modern individual chart a shift from a human experience of good and evil forces that swirl around in the ether – so that the moral choice is whether to latch onto the spiritual or social good or evil – to an awareness of the good and evil impulses within our selves.

Certainly Renault’s character’s lag behind, in their stoic simplicity, the complex fragility of, for instance, the protagonist of Hamsun’s Hunger. They can be buffeted by Fortune, but the evil of the world does not reach up, at least, not convincingly, from inside their own skin.

A Milieu Meticulously Portrayed

But if the characters, though enjoyable, are not utterly convincing, their milieu is meticulously portrayed. Our hero, Alexias, is selected to run at the Isthmian Games for Athens. His lover Lysis is to compete in the Pankration. Alexias is aghast to discover that Lysis’ opponent in this combat sport is to be ‘a mountain of gross flesh, great muscles like twisted oakwood gnarling his body and arms.’

Alexias is disgusted:

…at the sight of a man too heavy to leap or run, who would fall dead if he had to make a forced march in armour, and whom no horse could carry … This man had sold grace and swiftness, and the honour of a soldier in the field, not caring at all to be beautiful in the eyes of the gods, but only caring to be crowned.

Often Renault is able to open up historic perspectives that feel authentic, as here, where practical, aesthetic and religious values coalesce in the physique of young men. She is careful, too, to cast Alexias’ distaste as that of an older generation, fashions changing for the ancients as they do for us. And there is something else in it, the refined aristocrat deploring the incursion of the uncultivated rabble.

There is a parallel with the fading glory of the disinterested amateur athlete through the twentieth century, leading to the triumph of what could be called the grubby commercialism of the professional. We should not forget that Athenian democracy was the preserve of an elite.

Elsewhere Renault again seems to strike an authentic note when Alexias interrogates Socrates: ‘“Why?” I asked; for with him it came naturally to ask a reason.’ But this time the reason is that ‘something had made a sign to him’. This ‘something’ is usually called Socrates’ Daimon, a ‘prophetic voice’ that warned him against certain actions and also helped him guide his friends.

This is a side of Socrates, or at least of the character ‘Socrates’ bequeathed to us in Plato’s writing, sometimes glossed over. Fans of the Enlightenment like to speak of Ancient Greek culture as the first great flourishing of rational critique, of reason over faith. They have reason to. But there was more going on than that (and isn’t there always more going on than we can fit into our speech?).

In The Last Days of Socrates Plato reports the inventor of Socratic dialogue, the model of rational discourse, as saying of it:

This duty I have accepted … in obedience to God’s commands given in oracles and dreams.

Besides seeing his own philosophising as a divine duty, divinely given, he speaks in that book of religion more generally:

When any man dies, his own guardian spirit, which was given charge over him in his life, tries to bring him to a certain place where all must assemble, and from which, after submitting their several cases for judgement, they must set out for the next world.

The daimonic aspect of Socrates may well be more influential than that of rational discrimination, crucial as it was in the development of Neoplatonism and, via that, of the Christian theology that has so dominated much of the world’s thought up until our own time.

Renault nods heavily to this with an uncharacteristic anachronism. In the aftermath of the overthrow of the Thirty Tyrants, the Athenians are celebrating the reinstatement of Democracy. Plato, ever the aristocrat, warns against too great an admiration for the Demos, a concept something like what we would now call ‘the People’ (or, at times, ‘the Mob’):

Even if Zeus the All-Knowing were to put on earth this perfect man we have postulated, would he love the Demos? I think not. He would love knight and commoner, slave and free, Hellene and barbarian, even perhaps the wicked, for they too are the prisons of God-born souls. And the Demos would join with the tyrants to demand that he be crucified.

Where Have All the Good Men Gone?

If I have criticised the realism of Renault’s characters, I should also acknowledge that her approach to them is not wholly realist. The inevitable anachronism of the historical novel itself, always already outside of the time it tells of, lends itself to the legendary – as the future does for Star Trek. Characters who are a long time ago, in a galaxy far far away*, or once upon a time, are a step away from reality, a step into our dreams.

This book names real people, but those names are now somewhat foreign to their persons, coalescing around the written works produced by or speaking of them, and around what many generations and nations have made of those works since. Furthermore, Renault wrote other books that could be called historical in their efforts of fidelity to records written and archaeological, but featuring characters from the myths of Theseus: the man himself, Ariadne, Minos, Hippolyta… It isn’t a huge leap from historicising mythical figures to mythologising historical ones.

In this context I was very willing to indulge Renault’s idealised heroes and, in fact, enjoyed spending time with characters so fine and upstanding. Sometimes we all feel Bonnie Tyler’s need. The Last of the Wine accomplishes what historical novels should with flair, convincingly evoking a culture foreign in time and place, and in the same gesture holding a mirror to Renault’s contemporary society.

* yes, yes, that’s Star Wars, not Star Trek