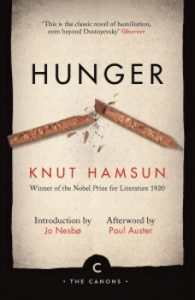

Hunger

Knut Hamsun

1890

1996 in translation by Sverre Lyngstad

‘The whole modern school of fiction in the twentieth century stems from Hamsun’, said Isaac Bashevis Singer. This, Hamsun’s first and most famous novel, is nevertheless about that archetype of Romanticism, the starving artist in his garret. And when I say starving:

There was a merciless gnawing in my chest … I pictured a score of nice, teeny-weeny animals that cocked their heads to one side and gnawed a bit … bored their way in … without haste, leaving empty stretches behind them.

But this life of poverty is not compensated for by a bohemian freedom to create. Rather, the weakness of the artist’s undernourished body impairs his powers of concentration, blanks and deranges his mind, until all he can do is peer at the page he writes on, unable to understand even his own words: ‘the strange, trembling letters which stared up … from the paper like small, unkempt figures’.

Hunger can be looked on as in part a satire on the Romantic artist who rejects bourgeois convention to slum it with the poor and contemplate the muse. Has this artist chosen to be beyond the pale of social norms or has he been debarred from them by his poverty? His musings seems to the reader a perverse distraction from the more pressing questions of whether he will have a roof over his head and food in his belly.

As were the Romantics, Hamsun is concerned with emotion and irrationality, spontaneous and immediate response to people and nature. But his artist, rather than finding in this a bridge to the Sublime, divine, or some Platonic ideal of Beauty, finds no answers, only encroaching madness, despair and humiliation.

Like many millennials, Hunger‘s protagonist has enough education to be ambitious for a bourgeois life, but not the resources to achieve it. He applies for work, he works hard on his writing, he lives frugally, and so can’t understand ‘why [his] prospects simply refuse to brighten up.’ He is one of those who in the modern age, moving from the country to the city, has ‘merely acquired new wants without being able to satisfy them’, a formula for resentment – or ressentiment, to use a favourite word of Nietzsche’s, who was a favourite philosopher of Hamsun’s.

The unnamed anti-hero leaps from fits of misplaced and self-harming pride to abject submission and humiliation. Asked for some change by a tramp, he immediately visits a local pawnbroker, gets some money for his waistcoat, and returns to give most of it away. The visible signs of poverty on our hungry man give the tramp pause and the coins have to be forced on him.

Later, the thought crosses the anonymous starveling’s mind of asking for money from a newspaper editor he submits to. This lapse is enough for him to punish himself by running full pelt until he can run no longer, at which point, ‘to torture myself properly I got up again and forced myself to remain standing, and I laughed at myself and gloated over my own exhaustion.’

Yet following confrontations with others, he goes away and reflects and weeps and begs forgiveness in his heart. At other times he is silent when insulted, knowing that to be the price of his night’s shelter. There is a mutuality to excesses of pride and shame: as Blake has it, ‘Shame is pride’s cloke.’ Hamsun’s character won’t let go of the prideful idea that he is, or should be, in charge of his destiny, and is ashamed of his real condition. That is why he looks down on the tramp, who looks to him ‘decrepit’ and ‘like a large, hobbling insect’, and why he tries to prove his higher status by an act of magnanimity.

The lead character, despite his suffering, shows no interest in challenging the structure of the society he struggles to navigate. Rather, he has internalised it, rejecting any sense of solidarity with other poor people and often being repelled by them, and by signs of them:

‘…the storage shacks and the old stalls with second hand clothing, were a real disgrace to the place. They spoiled the entire appearance of the marketplace and were a blot on the city – ugh, away with the junk!’

Hamsun was not concerned with writing an improving novel, or a story with a social conscience à la Dickens. In fact, he expressly wanted to ignore the environmental and social causes of human behaviour. These were the concern of Naturalism, a major literary trend of the time, which aimed to treat people from a scientific perspective, discovering the underlying laws that make them function. Hamsun had no time for it, instead choosing to focus on the vagaries of human subjectivity. Published in the same year as Hunger, William James’ The Principles of Psychology introduced the term stream-of-consciousness, which was soon adapted to describe the narrative technique Hamsun was a pioneer of.

Hamsun’s character embraces his irrationality, acting from caprice rather than enlightened self-interest. He spurns opportunities to make money and assuage his hunger. Just so that we realise the extent to which he asserts his freedom from all convention, whether human or cosmic, on seeing a cart full of potatoes he swears ‘in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost that they were cabbages.’ At times he seems to relish his ‘alienation from [him]self’.

In the afterword to this edition of Hunger, Paul Auster says (quoting Beckett) that Hamsun ‘admits the chaos’. He goes on to argue that by providing no salvation for his character, and no clear conclusion to his novel, that Hamsun was doing something new with art. By failing to be about Society, or any other object, Hunger inaugurates ‘an art that is the direct expression of the effort to express itself.’

While this is meant as a compliment, it is uncomfortably resonant with a passage from Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction:

‘Fascism attempts to organize the newly created proletarian masses without affecting the property structure which the masses strive to eliminate. Fascism sees its salvation in giving these masses not their right, but instead a chance to express themselves … This is evidently the consummation of “l’art pour l’art.” Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic.’

It might seem rash to read this political stance into the novel as a whole. After all, Hamsun is describing a fictional character. And yet… Certain lines from Hamsun’s letters suggest that Hunger is semi-autobiographical: ‘I didn’t eat for four days on end, I sat here chewing dead matchsticks.‘ When Hamsun, looking for his lucky break, gave the manuscript of Hunger to the critic Edvard Brandes, he appeared so gaunt and impoverished that Brandes, reading the tale of privation later that day, leapt up and ‘ran like crazy to the post office‘ to send the suffering Hamsun money.

More ominously, the sudden and absurd turns of thought and behaviour detailed in Hunger may also have been Hamsun’s: ‘The kind of oddities Dostoevsky has written about in the three books by him I have read … are something I live through daily.’

And most damningly, Hamsun was a literal quisling. He applauded the Nazi occupation of Norway and championed the head of its collaborationist regime, Vidkun Quisling. He met with Hitler and Goebbels, even gifting Goebbels his Nobel Prize medal. His standing in Norway, as both a giant of its literature and a traitor to the country, has been troubled ever since.

So is Hunger itself a fascist work? I see Hunger as describing a man’s struggle with the irreconciled forces of modernity, under which people retain a desire for salvation after having lost faith in God and tradition. The modern soul feels responsible for saving itself while knowing it has no power to do so.

Hunger dramatises the absurd condition of the modern, the condition that Camus later diagnosed in The Myth of Sisyphus: its anti-hero ‘stands face to face with the irrational. He feels within him his longing for happiness and for reason. The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world.’

The dilemma of modern life opens up many paths, and while Hunger doesn’t tell us which to go down, in the histrionic and egoistic response of its protagonist to his society, I think I glimpse fascism on its horizon. After all, anger and violence are as essential to modernity as is Progress. Auster pictures Hamsun’s modern, absurd man walking out of this book and ‘straight into the twentieth century’ – where we know that waiting for him, along with moon landings, civil rights movements and national health services, were nuclear bombs, world wars and final solutions.