The Peterloo Massacre

Robert Reid

1989

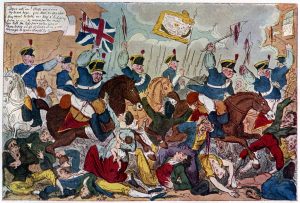

This year marks the bicentenary of the Peterloo massacre. On the 16th August 2019, armed cavalry charged a tightly packed crowd of well over 60,000 people who were gathered in St Peter’s Fields, Manchester, to call for political representation. At least 18 were killed and over 650 injured, many severely.

The fight for history began immediately. James Wroe, writing in the Manchester Observer, compared the murderous assault on unarmed men, women and children, with bitter irony, to the culmination of the Napoleonic Wars at the battle of Waterloo four years earlier:

It is rumoured, and we believe it correct, that orders have been sent to an eminent artist, for a design, to be engraved for a medal, in commemoration of Peter Loo Victory.

For his trouble he was imprisoned, and his newspaper was harassed by the courts and police until it was forced to fold.

The British establisment was terrified by the example of the French Revolution (though not terrified enough to share the wealth they jealously hoarded). Dissenting publications were prosecuted. Public assemblies were outlawed. Paid spies informed on their neighbours. According to Reid, even before Peterloo, Britain was ‘closer in spirit to that of the early years of the Third Reich that at any other time in history’. And the forcible curtailment of freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly, worked, to a degree.

Following the massacre, rioting broke out – as might be expected – and in the city of Manchester was swiftly put down by troops who shot and slashed at civilians. Some unrest continued into the next day in neighbouring towns, but there was little more violent reaction. Those attacked at Peterloo, and their many sympathisers throughout the country, went on to arrange a series of peaceful protests and pursued the perpetrators through the courts.

Their restraint in the face of violence was the more remarkable in its contrast to that of the state in the face of speeches and petitions. If the vast crowd had indeed been a tinderbox of revolutionary sentiment, one might have thought that the unprovoked murder of many of its constituents would have been just the spark to set it off.

The government and the courts, of course, ignored these lawful attempts at redress. In fact, it was the leaders of the demonstrations at Peterloo who were arrested, tried, and jailed. The British state so successfully stifled public reportage on the reform movement that the establishment has been able to continue to downplay the significance of Peterloo to this day.

The traditional historical focus on top-down change – that dictated by kings, queens or parliaments, or by military force – dovetails nicely with the refusal of Lord Liverpool’s Tory government to acknowledge the Peterloo protestors. Today’s Tories often take this tack. Lord Lexden OBE, Official Historian of the Conservative Party, thinks it was a lot of fuss about nothing and implies that the deaths didn’t amount to anything so awful as a massacre by belittling the word with quotation marks.

He believes that at the time, ‘everyone except a small radical minority believed that the demanding tasks of government should be in the hands of an elite’ – ‘everyone’ here being an unconscious euphemism for everyone that matters, not including small minorities represented by at least 60,000 people gathered to demonstrate out of a population of less than 500,000 in Manchester and the surrounding towns.

He does go so far as to smack the naughty Manchester magistrates on the wrist by suggesting that they acted ‘imprudently’ when ordering mounted troops to forcibly remove the crowd. In the Daily Mail, Dominic Sandbrook was prepared to call it a massacre, though also ‘almost certainly an accident’ and, actually, ‘by the standards of Britain’s neighbours, it was barely a massacre at all.’

The lack of concrete gains by the abused demonstrators means that Reid can write: ‘Peterloo was to have no effect whatever on the speed at which [their] demands were met.’ Jacqueline Riding, in her own take on these events, Peterloo, can say no more about their historical impact than that they ‘certainly drew national attention to the conditions of the working man, woman and child in the manufacturing districts of Great Britain.’

One result of this official indifference to Peterloo is the lack of public recognition afforded it. A monument was partially completed in 1842, but fell into ruin and was demolished in 1888. A blue plaque, on the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, evasively noting the gathering of a crowd and its ‘subsequent dispersal by the military’, was replaced in 2007 by a red plaque that states the relevant facts clearly.

The approaching bicentenary has galvanised efforts to remember Peterloo. Publishers have reprinted books on the subject (including Reid’s); the excellent People’s History Museum has a new mural; Mike Leigh (despite Manchester critic Danny Moran’s reservations about the film Peterloo) is telling the story to a new generation of cinema-goers; and The Peterloo Memorial Campaign is agitating for a permanent monument on the site.

These battles over the significance of Peterloo are a subtler continuation of the fight for power of which it was a manifestation. Those in power prefer to believe that progress is something benevolently granted to the masses as they become responsible enough for it, while those out of power hold to the notion that progress is wrested from the rich through popular struggle. Something like this historical divide in British politics, and its crystallisation in accounts of Peterloo, has been noted in the Economist (which with its usual complacence about the status quo claims the centre ground as though to do so is politically neutral and non-ideological).

To nail my colours to the mast (if you hadn’t noticed already), I am for the Left, and for Peterloo as a significant event for the history of the UK. If the government did not immediately pass legislation conceding to workers demands, did the political repression at Peterloo and during its aftermath contribute nothing to people’s appetite for reform?

The politically motivated closure of the Manchester Observer left a vacuum filled in 1821 by the Manchester Guardian, founded by John Edward Taylor, an eyewitness of the massacre, to ‘advocate the cause of Reform’, which it does, more or less, to this day. The Chartists took inspiration from Peterloo: the massacre was cited as an inspiration by Feargus O’Connor, one of the Chartism movement’s major leaders, and was remembered on banners at their meetings. And though the Chartists themselves did not have their demands met before the movement foundered, five of their six ‘radical’ proposals are now fundamental elements of British democracy. Without the resources to simply put their desires into effect, the results of popular movements accrete organically and over long periods of time, changing the way a society sees itself before changing its laws.

Reid doesn’t play down the wreaking of violence on a peaceful crowd, nor does he wear his political heart on his sleeve. He places the blame for the massacre on conflicting messages from the national government and weak leadership of the civil and military forces by local government. The fault in this view appears to lie in poor administration of crowd management.

But to assume that the crowd needed to be managed is to take the side of the power the people were resisting. It is a technocratic view, common to a number of accounts of Peterloo and perhaps illustrated most starkly by the faithful Tory Lexden: ‘the resources and institutions at [the government’s] disposal made it impossible to avoid death on a small scale very occasionally.’ This view ignores the capacity of people to act under their own authority – precisely the authority they were asserting by gathering on St Peter’s Field to demand change.

Shelley wrote The Masque of Anarchy ‘on the occasion of the massacre at Manchester’, yet due to concerns about the political climate it wasn’t published until 1832. Shelley’s poem casts, not the radicals, but the British establishment as Anarchy: ‘splashed with blood … he wore a kingly crown’. The rich and powerful act in their own interest, ignoring the righteous laws of heaven which can’t ‘be sold / As laws are in England’.

What right did the government and their magistrates have to police by violence the gathering of their fellow citizens in the first place? They were willing to sanction violence to maintain order – an order out of which they did very well – because they feared the potential violence of those their order oppressed. And this prejudice against the violence of change, this blindness to the violence that keeps things going on the way they are: this is the wider question – valid for us, today – that is left unexamined by a nitpicking focus on chains of command, on administrative procedure.

Peterloo was a moment in which the violence that maintains the establishment was made visible, and that it reminds us of that violence is enough to make it significant in every generation that remembers.

The last word to Shelley:

Let a vast assembly be,

And with great solemnity

Declare with measured words that ye

Are, as God has made ye, free