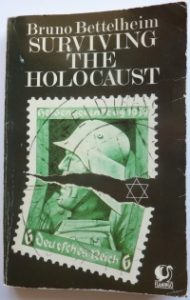

Surviving the Holocaust

Bruno Bettelheim

1986

Bruno Bettelheim survived Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps. After escaping Nazi Germany he directed a home providing for the care and rehabilitation of disturbed children, becoming a world-renowned psychoanalyst and expert on autism. He was a brilliant writer and had many books published besides this influential collection of essays. His The Uses of Enchantment: the Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (referenced on this very blog), won, in the USA, both the National Book Award and National Book Critics Circle Award.

After he died, another narrative emerged. On emigrating to the USA, Bettelheim had taken advantage of the chaos that World War II introduced among official records to invent an academic background in psychology. He was then able to take up the post of professor in that subject at the University of Chicago, and subsequently to be appointed Director of the institution’s Orthogenic School. A former student of the school took exception to a posthumous description of Bettelheim as ‘a great Chicagoan’, and their letter to the Chicago Reader provoked more correspondence from students and staff alike, describing systematic physical and emotional abuse at his hands. Eagle eyes spotted that chunks of The Uses of Enchantment were plagiarised. His theories on autism are now largely discredited.

What, then, to make of Surviving the Holocaust? These essays analyse the concentration camp experience and the totalitarian nature of Nazi rule. They carry the moral authority of eyewitness testimony and persuasive, scholarly expression. They are written by someone whose academic qualifications and professional integrity have been found lacking.

What Survives the SS

Even within his lifetime Bettelheim met controversy. His essay ‘Individual and Mass Behaviour in Extreme Situations’ was first published in 1943 in an attempt to publicise the fact of concentration camps. He wrote that when he tried to speak of them:

‘I was accused of being carried away by my hatred of the Nazis, of engaging in paranoid distortions. I was warned not to spread such lies.’

In later years, the essay would be criticised from a different angle, focusing on his assertion that the long term prisoner reached the point of ‘chang[ing] his personality so as to accept various values of the SS as his own.’ Bettelheim is balanced, acknowledging that this interpretation is partial and that these very same prisoners ‘who identified with the SS defied it at other moments, demonstrating extraordinary courage in doing so.’

But elsewhere there is less balance. ‘The Ignored Lesson of Anne Frank’ discusses the famous diarist, and the play and film based on her writing, as unhelpful models for survival. Bettelheim contends that the Franks’ choice to go quietly on living as a family, hiding away in the wainscoting like mice, expressed in microcosm the majority reaction of European Jewry: ‘passively waiting to be rounded up for their own extermination.’ To make the point as clear as can be, he is reported to have asked a mainly Jewish audience: ‘Anti-semitism, whose fault is it?’ And then to have answered himself, ‘Yours! Because you don’t assimilate, it is your fault.’

Bettelheim’s denunciation of ‘Jewish’ passivity stands in contrast to his account in ‘Surviving’. In this essay, he emphasises the arbitrary nature of survival in the Nazi camps, and particularly in the death camps (though he was fortunate enough to be released before these were established). While he writes that ‘To stay alive, prisoners had to try at all times to be active in their own behalf,’ he at the same time scorns ‘the pretence that what the prisoners did made their survival possible.’ Only the liberation of the camps by the Allied armies prevented the eventual death of them all.

‘Surviving’ is in part a response to the ideas of Terence Des Pres. In Bettelheim’s reading, this scholar of the Holocaust thought that survivors, having been forced to ‘live beyond the compulsions of culture’, were then able ‘to embrace life without reserve’. By contrast, Bettelheim asserts that prisoners reduced to what he characterises as amoral, animalistic survival behaviours didn’t last long, whereas those acting in solidarity improved their chances.

Taken together, that survivors were active even in captivity, that they were not the final arbiters of their own fate, and that even minimal remnants of culture held them together: these beliefs appear an implicit endorsement of the Franks’ approach to persecution. Feeling, perhaps, otherwise powerless, they took steps to preserve their social unit for as long as possible. This is not necessarily to say that Bettelheim was inconsistent – the circumstances were different, and no prescription is universal. But that he proposed in such strong terms two views in such tension with each other might suggest some internal conflict.

His lauding, at least in this essay, of the importance of culture is compelling. Why, after all, did the Nazis separate families from each other in the camps? In order to more effectively dehumanise them. It is disconcerting, then, to consider that the children Bettelheim cared for at the Orthogenic School boarded there, separated from their families, and that he appears to have despised those families. He believed children’s problems largely stemmed from mothers and fathers it would be best for them to escape.

Richard Pollack’s brother had been at the school and when he died in tragic circumstances Pollack visited Bettelheim. As reported via Molly Finn, he:

‘heard his father dismissed as a crude schlemiel, his mother vilified “with astonishing anger,” described as the cause of all his brother’s problems and scorned as a “Jewish mother”.

This wasn’t Bettelheim’s view of one family only:

‘All my life I have been working with children whose lives have been destroyed because their mothers hated them.’

Pollack later devoted a book to, as he saw it, exposing Bettelheim as a charlatan. Ex-staff characterised the psychoanalyst’s work with the children as ‘instruction through terror’ and the ‘Nazi-Socratic method.’ The frightening possiblity raised here is that Bettelheim’s diagnosis that prisoners came to accept SS values may be anecdotally confirmed in at least one case: his.

Feet of Clay

And yet, Ronald Angres, who suffered under the Orthogenic School’s regime, does ‘not believe that Bettelheim first learned either his manner or his methods from the SS in the camps.’ He was already the man he was in the USA before his interment. Bettelheim seems monstrous either way: the survivor who learnt to control others as he had been controlled, or a man already base who posed as a martyr to con his way to wealth and status.

But if we judge that in these essays he has judged too harshly the response of the Jews of Europe, must we, therefore, also not judge his own response too harshly? Timothy Pytell argues that the critique, offered by Des Pres and others, that ‘Bettelheim … somehow accurately or inaccurately captured Holocaust experience is an unfair burden to place on [him] … The real question is why would we expect [him] to get it right?’

Bettelheim does take on the role of academic observer in these essays, but why do we take him at face value? He acknowledges that this approach was in large part driven by his personal demons: ‘Trying to be objective became my intellectual defence against becoming overwhelmed by these perturbed feelings.’ ‘Trying’ is the operative word and to read this book again, considering it as a form of self-therapy for Bettelheim, would be an interesting exercise.

Then again, even Pollack acknowledges that some students of the Orthogenic School believe they benefited from their treatment. Bettelheim’s successor as Director of the school, Jacquleyn Sanders, has defended his legacy. Bettelheim’s extensive self-mythologising has generated a prodigious number of articles, some excoriating him as an irredeemable villain, others ambivalent, keen to salvage his talents as well as recognise his sins.

And, though this in no way excuses the abuse that Bettelheim did perpetrate, we ought not to be complacent about our own treatment of autistic children. Right now, in the twenty-first century UK, people with autism and severe learning disabilities are being imprisoned and abused, receiving still worse ‘care’ than the Orthogenic School provided.

Confounded Codas

Bruno Bettelheim killed himself in 1990, at the age of 86. On first learning this, ignorant of his dark side, I was reminded of my feeling when I read that Primo Levi, another writer of the Holocaust, perhaps the greatest, died by suicide. I thought it a desperate tragedy that after having the fortitude, the sheer will, to survive the death camps, and then to bear witness to that trauma in superbly humane books, that, as Elie Wiesel put it: ‘Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years later.’ It seemed as though the Nazis had ultimately defeated him.

Then I picked up from some article or other the notion that Levi had other things to concern him besides the Holocaust. Indeed, he was undergoing a period of poor health and was also oppressed by the decline of his mother and mother-in-law, both living in his home under the constant care of a nurse as they fell ever further into senility. Muddying the waters still more, serious questions have been raised as to whether Levi’s death was due to suicide at all. He may simply have fallen: an old man recovering from surgery, a low banister.

Bettelheim certainly did kill himself. He took some pills and put a plastic bag over his head. Previously, he discussed suicide at length both with his daughters and in interviews with the Los Angeles Times. But his morbid preoccupations were to do with the physical and mental debility caused by a succession of strokes, not his experiences in the camps:

‘if I could be sure that I would not be in pain or be a vegetable, then, like most everyone, I believe I would prefer to live.’

His daughter Naomi traced the causes of his suicide, at least partially, even to before Nazi persecution began:

‘There are many, many factors why my father did choose this route, going as far back as his upbringing in Vienna. There was quite a preoccupation with suicide in Austria when he was young.’

Reverence Vs. Empathy

These Holocaust survivors fill me with a sense of awe involving deep sadness and horrified fascination. They are people who have seen a hell on earth. But perhaps this reverence is a problem. After all, to say ‘Holocaust survivor’ is to name just one aspect of whole persons, such as, for example, Primo Levi and Bruno Bettelheim. The Holocaust hangs over our thoughts and feelings about them. We are liable to assume it was some sort of lesson, that it gave them courage, wisdom, compassion, that it defines the rest of their lives.

But we may be doing not much more than reading tea leaves. And those who lived through it may not have been much more able to comprehend their experience. Many of those who were murdered in the Nazi death camps, and who survived them, will have been stupid, mean, greedy, deceitful – even murderers themselves – as well as whatever else they were or are. To see those people only in the light of that aspect of their lives is to ignore their full humanity, a fault that is the shadow, if a pale one, of that which led to their ordeal.

Bettelheim’s story remains fascinating despite, or still more because of, the kinks that appeared in it after his passing. The lessons the world thought he had left it turn out to be slipperier, suppler than had been imagined. I still struggle with what to make of the man and his work, perhaps only that we should doubt even the authority of suffering. Nevertheless, by extending alongside that doubt our empathy, a quality that, if he bestowed it unevenly, Bettelheim always celebrated, there is much to learn from him.

Intriguing and disturbing article. I do agree with you on most of your points. I do, however, give some credence to Bettleheim’s contention that the initial purpose of the concentration camps were more of a deterrent than an extermination vehicle. My research indicates that the earlier detainments were often temporary, a warning to leave with their families after relinquishing most of their assets. It was called the European plan, I believe. It must have been a difficult decision to make to relocate as your article suggests. The added difficulty was that immigration access was sharply curtailed in relatively short order. Ships took off loaded with affluent, educated Jews seeking safe harbor only to be denied entry. The United States, my own country, stopped accepting Jews early in the war. The novel, Ship of Fools, provides a fictional account of this. The reality is that Hitler was quoted as stating that it was proof that no other country wanted the Jews, which ultimately led to his understanding that he’d been given carte blanche to do whatever he wanted in terms of the Jewish question.

It’s an interesting point you raise about the attitude of countries beyond Germany to refugees and particularly Jews. The enormity of what the Nazis did tends to obscure the complicity of the wider world in their prejudice. Hannah Arendt talks about this in Eichmann in Jerusalem, noting that far fewer Jews died in Denmark and Bulgaria than in other Nazi occupied countries. That was purely because the local populations refused to cooperate with, and actively opposed, the rounding up and incarceration of their neighbours. In some countries the locals were enthusiastic participants. My nation, the United Kingdom, has very fine thoughts of itself in relation to WWII, but I think this has been enabled by the fact that when the Nazis steamrolled the Allied armies in the early stages, they were prevented from occupying the UK, as they did the rest of Europe, by the sea. Had Britain been occupied, its inhabitants would have faced some hard moral choices, and there’s no guarantee that most would have made good ones.

I discovered a typewritten letter Bettelheim wrote to my mother on Sept. 18, 1958 when my brother Arthur (diagnosed with autistim/juvenile schizophrenia) had been a student at his Orthogenic School in Chicago at the age of 5 and for several years and was making little progress.

In the letter he says “Arthur is terribly unhappy, unless continually catered to and permitted, without interference, to remain in his delusional world.” “I am afraid I must advise you to arrange for Arthur’s placement in a mental institution.” “The time will come when I will not just advise it, but have to request it.”

My brother was institutionalized from the age of 11 until the institutons closed and he now lives in a group home.

Thank you for sharing that fragment of your family history. Bettelheim’s advice sounds ominous, though I don’t, of course, know what your brother’s experience was like. However, shutting people away in institutions is generally an admission that we don’t have a good solution for dealing with them. Even today, in the UK, many people with severe autism are effectively imprisoned in care homes that offer inadequate care. Abuse within the ‘care’ system still occurs. I’m aware of one journalist in particular who writes on this issue: http://www.ianbirrell.com/tag/autism/.

I dare to hope that your brother didn’t suffer as some have, but being removed from your home at 5 years old is a suffering itself, whatever the reason, good or bad.