The Lady in the Lake

Raymond Chandler

1944

Philip Marlowe may be as well known as his author. He’s the quintessential private eye: at home on the mean streets of LA; cool in the company of bent cops, dissolute fraudsters and seedy pornographers. He’s named after Marlowe House, of which Chandler was a member while at prestigious public school Dulwich College, in the affluent suburbs of London. At the outset of his career, Chandler worked briefly at that bastion of the British establishment, the Admiralty.

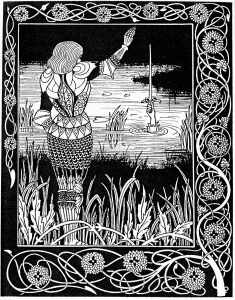

These upstanding influences have been read into Marlowe, who Chandler himself famously described as a ‘shop-soiled Galahad’. It was important to Chandler that his hero be a man of honour, incorruptible. Galahad, knight of the round table, was just that: the hero pure enough to be granted a vision of the Holy Grail.

But Galahad was an interpolation into Arthurian legend by pious Christians. In earlier Romance tales characters wrestle with the conundrums thrown up as feudal traditions begin to fade and the individual economic actors of the Enlightenment appear on the horizon. Knights Tristan and Lancelot try to reconcile the honour that demands fealty to their lords – Kings Mark and Arthur – with the imperatives of their love for their lords’ wives – Isolde and Guinevere.

The pre-Galahad Grail knight, Perceval, is pure, but his innocence is an impediment. Given an early glimpse of the Grail by its keeper, the Fisher King, his ignorance prevents him from using his power to save the King and win the Grail. Only suffering through long and lonely quests brings him the maturity to fulfill his destiny.

Galahad, though. In L’Morte de Arthur, by Thomas Malory, he arrives in the company of twelve nuns, little more than a child, ‘seemly and demure as a dove, with all manner of good features’, and immediately the other knights say ‘this is he by whom the Sangreal [Holy Grail] shall be enchieved’. Then he knocks them all down in the joust. Oh, and his lineage ‘is of the ninth degree from our Lord Jesu Christ’. Galahad sails woodenly through his quest, so good that we know he’s going to overcome every challenge. No dramatic tension; no character development.

This is not an auspicious model for any protagonist, let alone a hard-boiled tough guy. And it is the case that Marlowe is unusually dramatically inactive. Things happen to and around him. As The Lady in the Lake (note the Arthurian pun) comes to a close, there is the obligatory shoot-out with the unmasked murderer. Marlowe watches while another character faces off with the bad guy, no idea who will be quicker on the draw. Luckily, the other guy saves the day.

But whereas I found Galahad insipid in comparison with his full-blooded forebears, my discovery of Marlowe was a breath of fresh air after Hollywood’s endless litany of smug action heroes. He’s the template for the cool and wisecracking types of a thousand blockbusters, his dialogue echoed in them to this day. Third-rate, insipid echoes.

Mind you, the silver screen already had its conventions by the time Chandler was writing, as Marlowe recognised in The Big Sleep:

‘His voice was the elaborately casual voice of the tough guy in pictures. Pictures have made them all like that.’

Marlowe has the witty backchat that all lead action parts do, but whereas others are perpetually crowing over their effortless mastery of any given situation, he doesn’t puff himself up. If he wants to bring someone down a level, it’s only to his own. Not that he’s as humble as, say, that later exemplary detective Columbo, but they do share a defining trait: doggedness. Marlowe’s pride is in his dedication to his job. He doesn’t win the money or the fame or the girl or the glory. He gets the job done.

Chandler’s work may fit neatly into the noir, and his hero is jaded and world-weary. But he’s also funny. Often it’s black humour. Often it’s just funny:

- ‘The blonde was strong with the madness of love or fear, or a mixture of both, or maybe she was just strong.’

- ‘I waited in the dark, with the flash in my left hand. A deadly long two minutes crept by. I spent some of the time breathing, but not all.’

This exchange from The Big Sleep could have bounced between the Marx brothers:

Gangster: ‘Is that any of your business, soldier?’

Marlowe: ‘I could make it my business.’

Gangster: ‘And I could make my business your business’

Marlowe: ‘You wouldn’t like it. The pay’s too small.’

Tom Cruise would say this with a twinkling eye, before effortlessly somersaulting past the gangster’s bullets and karate chopping him into submission. Because there’s a sense in which Tom Cruise is more like Galahad than Marlowe. Tom Cruise just has to be Tom Cruise to come out on top (and I use the actor Tom Cruise’s name to refer to a hypothetical character played by him because, of course, the studios employ Tom Cruise to be Tom Cruise). Marlowe’s work costs something of his character.

After he discovers more sordid details of the story behind the lady in the lake (SPOILER: she’s dead), he gets a phone call. Finishing it:

‘I stood there holding the telephone half-way between my ear and the cradle. Then I put it down very slowly and looked at the hand that had held it. It was half-open and clenched stiff, as if it was still holding the instrument.’

In a passage that gives that book its name, he muses on the relative merits of death and life. If you were one of the victims:

‘You just slept the big sleep, not caring about the nastiness of how you died or where you fell. Me, I was part of the nastiness now.’

And then the penultimate lines of that novel:

‘On the way downtown I stopped at a bar and had a couple of double scotches. They didn’t do me any good.’

Marlowe doesn’t speak with a twinkling eye, and his quips are not triumphant. Which means I can accept and savour them, instead of, as in 90% of contemporary films, wanting both hero and villain to be struck down with leprosy or eaten by wolves – anything to put an end to their tedious cocksure banter.

The paucity of good writing in film is a theme well known to Chandler, having worked there himself. He was twice nominated for an Oscar, first via a co-writing credit on Double Indemnity, then as sole scriptwriter for The Blue Dahlia. His experience led him to write a long lament for writers in Hollywood and the degradation of their art:

‘That which is born in loneliness and from the heart cannot be defended against the judgement of a committee of sycophants. The volatile essences which make literature cannot survive the clichés of a long series of story conferences.’

I return to my overriding initial impression of Chandler: that I had glimpsed the Holy Grail of cool film dialogue (in a novel!), of which everything since is a fumbled and misconceived imitation.