The Comical Tragedy or Tragical Comedy

of Mr Punch

Neil Gaiman (text) & Dave McKean (illustration)

2006

For children, the crack of violence can be as sudden, vast and unexplained as that of thunder. There is no context, only danger. The Comical Tragedy or Tragical Comedy of Mr Punch explores the child’s sense of unknown forces out there in the adult world. And, in the face of fear, the ambivalent desire to come to know them. ‘Adults do what adults do; they live in a bigger world to which children are denied access.’ When does a child become ready – and willing – to enter the adult world?

Neil Gaiman sprinkles the lore and history of Punch and Judy shows throughout this book, starting with the title, which is lifted from Punch’s earliest known script. This was transcribed in 1827 by John Collier during a turn by the veteran performer Piccini, 82 at the time.

Piccini was one of many Italian puppeteers who toured Europe, bringing the traditional character of Pulcinella to new audiences and founding local variants of the character and his stories across the continent. The roots of the ‘little chicken’ (as one suggested derivation of his name has it) reach back at least as far as the Commedia dell’ Arte. This was a form of theatre established in Italy in the sixteenth century, based on improvisation around stock scenarios and characters represented by masks. Pulcinella was one of these. His mask is black with a hooked, bird-like nose and his back is often hunched. He is an underdog, spontaneous, crass, and typically gets one over on authority either by his low cunning or through dumb luck.

Piccini was one of many Italian puppeteers who toured Europe, bringing the traditional character of Pulcinella to new audiences and founding local variants of the character and his stories across the continent. The roots of the ‘little chicken’ (as one suggested derivation of his name has it) reach back at least as far as the Commedia dell’ Arte. This was a form of theatre established in Italy in the sixteenth century, based on improvisation around stock scenarios and characters represented by masks. Pulcinella was one of these. His mask is black with a hooked, bird-like nose and his back is often hunched. He is an underdog, spontaneous, crass, and typically gets one over on authority either by his low cunning or through dumb luck.

Commedia dell’ Arte means something like ‘theatre of the professionals‘ and it may be that this is why Punch and Judy performers are known as ‘professors’. They travel with a ‘bottler’, who collects money from the crowd, produce Punch’s voice using the kazoo-like swazzle and beat Punch’s co-stars with his slap-stick. While interesting, these details are a veneer on the dark heart of Gaiman and McKean’s book. Only one anecdote I discovered approaches it’s tenor: the tale of old Borgniet, head of a travelling puppeteer troupe, who swallowed his swazzle in 1866 and choked to death mid-performance, crying for help in Punch’s deadly voice. One wonders if he managed to wheeze out one last ‘That’s the way to do it…’

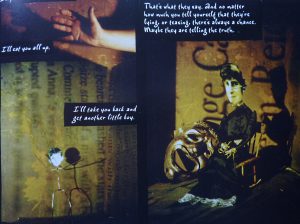

Punch has entered the language. ‘Pleased as Punch’, we say, and in Italy, people talk of Il segreto di Pulcinella: Pulcinella’s secret. This is an open secret – one which everyone knows, but pretends not to. The story of this book concerns an adult narrator looking back on his childhood and trying to make sense of his family’s unspoken past. As a boy he was told one thing and another about his grandfather’s madness, his uncle’s deformity: but not enough that was true to make sense of the violence he eventually witnessed. The boy struggled to understand something all the grown ups seemed to know but wouldn’t tell him. How is a child to know when adults are telling them the truth or not, or if they are, what part of the truth?

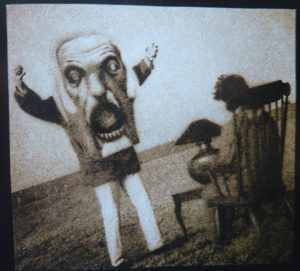

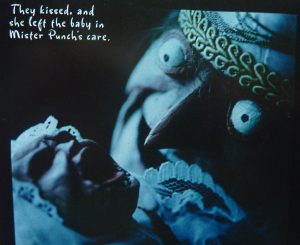

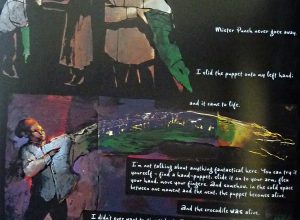

The artwork of Dave McKean is a shifting collage of traditional ink drawn comic panels, painting and staged photographs. It is evocative and frequently terrifying. The mix of materials suggests itself as a mix of representative, documentary and self-consciously staged modes, which resonates with the narrator’s effort to piece together the story of his family’s past from imperfectly remembered events, the recollections of others, and half-suppressed memories. ‘The path of memory is neither straight nor safe, and we travel down it at our own risk.’

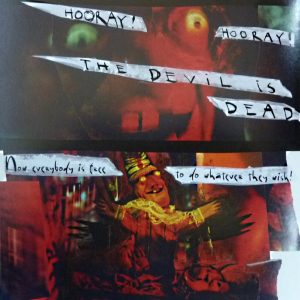

Memories of the Punch and Judy show are contested, both those we have, and those we believe our children may gain. There are concerns over the wife beating, baby murder and Punch’s flagrant ability to get away with his amorality. The policeman, the priest, the hangman, the devil: all these pursue him and try to persuade him to change his ways on pain of punishment. Punch beats them to death with a stick. So occasionally one council or another has chosen not to support a performance. Those who relish a bit of recreational indignation have got good mileage out of this, but for a change they have someone of good sense on their side; the noted liberal Charles Dickens:

‘In my opinion the Street Punch is one of those extravagant reliefs from the realities of life which would lose its hold upon the people if it were made moral and instructive. I regard it as quite harmless in its influence and as an outrageous joke which no one in existence would think of regarding as an incentive to any kind of action or as a model for any kind of conduct.’

That Dickens was moved to state such an opinion tells us that there were others and we can infer that disapproval of Punch is not a case of Political Correctness Gone Mad™ and the degeneracy of contemporary society, but rather part of a long and ongoing conversation. If there has been a decline in Punch’s popularity, it’s not down to his being banned (the clue to that is that he hasn’t been).

The question of evil, and of vicious punishment, is discussed by the psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim in his 1976 book The Uses of Enchantment. He stresses the importance for children that the baddies should meet what seem to adults horrifically cruel ends – think of the evil queen in Snow White who has her feet locked into super heated iron slippers and is made to dance, or Cinderella’s sisters, who have their eyes ripped out by vengeful birds. This is, says Bettelheim, what children want: to see that evil-doers do not prosper. He quotes Chesterton (always a good idea), ‘children are innocent and love justice, while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy.’

Justice isn’t exactly what we get with Punch, and Bettelheim does address evil more generally, noting that fairy tales speak to what in the child is ‘violent, anxious, destructive, and even sadistic’. In a section titled ‘Why Were Fairy Tales Outlawed?’ he explains that the terror and violence in such stories gives children a way to engage and come to terms with the darker aspects of their nature.

Gaiman and McKean’s Punch, though, is written for adults, and is a foreboding of the violence and death that await children as they grow into adulthood. The violence and death that are not fair, as Punch is not fair, and whose motivation may be obscure to the child, as Punch’s is stripped bare of any motive and appears to be simply the expression of what he is. The boy of their story is both repelled and fascinated by Punch, as he is by the family history that is kept from him, but which motivates a brutal scene that he wasn’t supposed to witness. This Punch is not fun for all the family.

The cartoon onslaught of the Punch performance, the revolving cast of victims, all resurrected in time for the next show, perhaps serve to take the sting out of death. Watching it, we may be tempted to say, as Krishna to Arjuna in the Baghavad Gita:

‘If any man thinks he slays, and if another thinks he is slain, neither knows the ways of truth,’ for we are eternal. And even if we were to be born again and again, to die again and again, ‘all things born in truth must die, and out of death in truth comes life. Face to face with what must be, cease thou from sorrow.’

We might read Punch as the eternal in us. Mr Punch is worn on the right hand: ‘He goes on, and on he stays … the others – the ghosts and clowns and women and devils, they come on and they go off.’ Our lives come and go, like those of the puppets – the divine hand simply moves on to animate another performance – the story teaching that something of us survives no matter what happens.

But that reading feels a bit of a stretch. Others are certainly possible. Punch’s most common adversaries are figures of convention and authority: his wife, the doctor, the policeman, the hangman. They all try to stop him doing just what he wants. The devil is the ultimate scourge of those who transgress beyond limits, and Punch defeats Old Nick too. Looking from this direction, the pantomime of Punch may be a cathartic experience of the secret desire to do away with authority, to overturn the parent in your own head, the superego, and let the id run wild. Maybe the lesson is that everything should have an end, and especially you.

There’s something hellish about Mr Punch’s relentless vitality. He escapes the law, the noose, the underworld, and remains undead among us.

‘Mister Punch never goes away.’