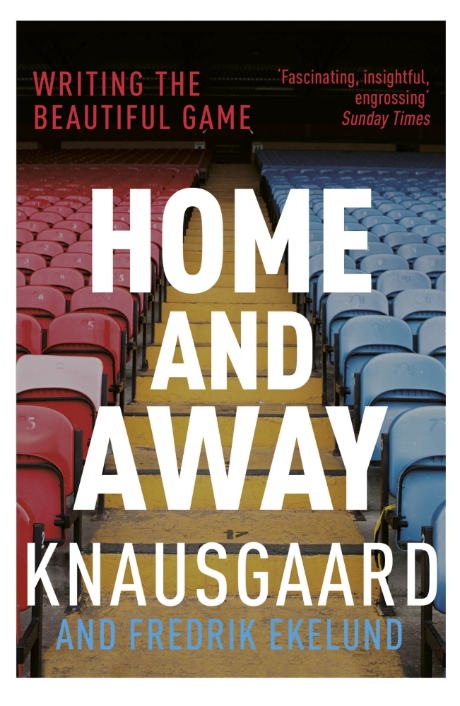

Home and Away

Karl Ove Knausgaard and Fredrik Ekelund

2016 (2014 in Norwegian)

As I prepare to wallow luxuriously in the month of football heaven that is the world cup, this book takes a look back at the last one.

On the face of it, it’s a cash-in gimmick. Two writers will watch the 2014 world cup and write to each other during it. Their emails will be published. Money for old rope, you might think. But it’s a gentle pleasure, a long conversation between interesting friends.

Ekelund is a Swedish novelist, poet and playwright who has written a book on the history of Brazilian football. He goes away to Rio to play footy on the beach and watch matches in rowdy bars. Knausgaard is the internationally famous Norwegian author of the intensely brilliant My Struggle series. He stays at home with the wife and kids watching games on his own and half-asleep when the kids have gone to bed and the chores are finished.

Already a fan of football, literature and Knausgaard, I was a sucker for this, and enjoyed the built-in tension of knowing that the unsuspecting narrators were gradually approaching the real climax of the 2014 world cup: the jaw-dropping 1-7 implosion of host nation Brazil in the semi-final.

Knausgaard lost points on my fan-ometer, although, to be fair (which is the sort of thing you have to do when talking about football), at the same time adding piquancy to the book, by admiring Italy, who win ‘so coolly, so urbanely and so cynically’ whatever it takes. Ekelund, sensibly, dislikes ‘these perfumed gravediggers of football’ and like me ‘few things make [him] as happy during a world cup as when Italy go out’ (a happiness denied to us this time round, ha ha). A great part of the appeal here is that these intellectual artists have the same arbitrary prejudices for and against teams and players as any other footy fan.

And this is how the book proceeds, Home and Away, the theme of one message setting up the reply, a series of one-twos, or like the middle-aged dance of plumply elegant Brazilians observed in a hole-in-the-wall bar. Though it would be stretching the point to say, as Ekelund does of the dance, ‘that everything else dissolves in the face of this beautiful couple’, the authors deliver an engaging and affectionate back and forth.

In discussion of the poetry of Tranströmer (2011 Nobel prize in Literature), Ekelund writes that it helped him through a dark time in his youth and Knausgaard delicately invites him to say more, until out spills the story of his father’s late-in-life revelation that he witnessed his own father’s sudden death. The effort of reflecting on his father’s suppressed trauma drains him, he feels he has been ‘laid bare’, a state not unknown to Knausgaard, notorious for novels-as-autobiography, unsparing in their candour. Of giving himself away in this book, he tells Ekelund ironically, ‘since it is a letter to you alone, I don’t regret a word.’

But much as you can expect meditations on life and literature here, the two friends are firm followers of the game. Besides the blow-by-blow accounts of tournament matches, they reminisce over the all day jumpers-for-goalposts marathons of childhood, the glories of amateur league games, and Ekelund reports on his Copacabana kick-abouts.

Striking true for me were the reflections on football community. Through match after match you can build real relationships with people you know only as footballers. You might have learnt little to nothing of their off-pitch selves – work? partner? children? – but you know how they stand up in the tackle, if they track back, if they’ll lay the ball off when you make a run. As the French winner of another Nobel Prize in Literature, Albert Camus, put it: ‘All that I know most surely about morality and obligations, I owe to football.’

And something is exchanged via sheer physical activity: if two of you sprint all out for the same ball, if someone knocks you over (without malice we assume), or vice-versa, then for that moment life’s relish is shared. When the whistle is blown, the next teams on the pitch shout ‘time’, or in younger days when the sun goes down, you return to yourself from the collective effort and in handshakes and terse acknowledgements like ‘played mate’ or ‘good game’ there is recognition that for the figurative 90 minutes football folded you together.

For Knausgaard, ‘When football is written about it is already over, and when the article is read there is no longer any value in the match; all that exists is the value of the writing.’ Fortunately, the writing here is good value.