The Conquest of New Spain

Bernal Díaz

1632

1963 in translation by J.M. Cohen

A Dream of a City

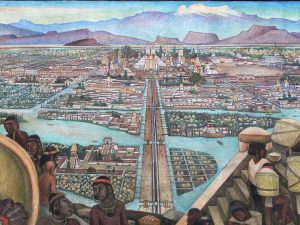

‘…when we saw all those villages and cities built in the water, and other great towns on dry land, then that straight and level causeway leading to Mexico, we were astounded. These great towns and cues [temples] and buildings rising from the water, all made of stone, seemed like an enchanted vision from the tale of Amadis. Indeed, some of our soldiers asked whether it was not all a dream.’

Within two years of Bernal Díaz’s first stupefied sight of it, the great city on the water, Mexico, known too as Tenochtitlan, was as if it had been a dream: the houses, the palaces, the temples, reduced to rubble. Soon, colonial buildings would be raised in their place.

Lightly moored to the land by three branching causeways, each two or more leagues long, it was closely packed with buildings. Some lordly houses were two-storeyed, the well-wrought walls framing internal courtyards and gardens; most were the smaller, humbler, mud dwellings of commoners, their flat roofs crested with the rich green of growing things. All the buildings shone with whitewash and were bordered with ruler-straight canals and well-swept footpaths. At intervals larger structures clustered around local temples, while the whole was dominated by a central zone which held a city in itself, marked by the shimmering bulk of pyramids and towers vivid with red and blue and ochre stucco.

Free Enterprise

Bernal Díaz Del Castillo was a nobleman born in 1492, as Cohen tells us, ‘the year in which Columbus discovered the New World’. First attempting to make his fortune in Tierra Firme (later Panama), then Cuba, Díaz was thwarted by tropical illness and the squabbling of the established colonials over who should have the fattest share of the ‘New’ World’s riches.

Enter Hernán Cortés, a descendant of impoverished gentry who had already built up some small influence in the Caribbean. When, in 1519, Cortés was made captain of a third exploratory expedition to what would become known as Mexico, Díaz, as a veteran of the previous two voyages, joined his company.

Cortés, though, ‘had nothing with which to meet the expenses of the trip, for while ‘he wore a plume of feathers, with a medallion and a gold chain, and a velvet cloak trimmed with loops of gold [and] looked like a bold and gallant captain … he was very poor and in debt’. He had slaves, even owned a gold mine, but spent his income to the last peso and beyond on fine clothes for him and his wife, and on wining and dining his friends. To raise loans from local merchants, he had to mortgage his estate.

This enterprise was formed under the authority of the Governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez, who had written to Spain requesting the legal right to conquer and colonise Mexico. Cortés, however, wanted to make the place his, perhaps conscious of what it would now take to keep up appearances and pay off what he owed. To that end, he purposely set off before a response had been received, in defiance of the Governor’s orders. In this way, he hoped to create a settlement in his own name, claiming ignorance of any title in the meantime conferred on Velázquez.

A petty ruse, but also the reason for one of the major historical sources of the period, the Cartas de Relacion, known in English as Letters from Mexico. For Cortés was now obliged to make his case directly to King Charles V, calculating that if he was able to deliver new lands, subjects and tribute, his insubordination would be overlooked.

These letters, then, were necessarily a propaganda exercise, extolling both the wonders and riches of Mexico, and Cortés’ efforts to bring them under the sovereignty of the Spanish Crown. And badmouthing Velázquez. The letters were printed and broadcast immediately on arrival in Spain, likely by arrangement of Cortés’ father. It is probably this attempt to sway public opinion that led to the letters being banned in 1527.

The historian W.H. Prescott wrote in 1843 that Díaz was, by contrast, ‘a most true and literal copyist of nature.’ This is quoted approvingly in Cohen’s introduction to this edition of The Conquest of New Spain. It’s true that Díaz is plainly spoken and his narrative feels immediate. Still, he composed it fifty years after the event, with similar, if less acute, reason to justify and glorify his actions as Cortés. Furthermore, this ‘copyist of nature’, according to Anthony Pagden, ‘borrowed far more than he was ever prepared to admit’ from Francisco López de Gómara, the first historian of the conquest. And this despite Díaz’s scathing treatment of rival chroniclers in his own book, in which he goes so far as to accuse Gómara of having taken a bribe to eulogise Cortés, leaving the other conquistadors, such as himself in the shade.

The Conquest of History

But with these caveats in mind, The Conquest of New Spain is a fascinating book. Many passages give a sense of the novelty of the encounter between civilisations that had until then lived in total ignorance of each other, together with a flavour of the past that they both now belong to:

‘…Tendile brought with him some of those skilled painters they have in Mexico and … he gave them instructions to make realistic full-length portraits of Cortés and all his captains and soldiers, also to draw the ships, sails, and horses, Doña Marina, and even the two greyhounds. The cannon and cannon-balls, and indeed the whole of our army, were faithfully portrayed, and the drawings were taken to Montezuma.’

‘They said that their ancestors had told them that very tall men and women with huge bones had once dwelt among them … and to show us how big these giants had been they brought us the leg bone of one, which was very thick and the height of an ordinary sized man, and that was a leg bone from the hip to the knee … We were all astonished at the sight of these bones and felt certain there must have been giants in that land.’

‘…five Indians came in great haste from the town to tell the Caciques who were talking to Cortés that five of Montezuma’s tax-gatherers had just arrived. The Caciques turned pale at the news. Trembling with fear, they left Cortés and went off to receive the Mexicans. Very quickly they decorated a room with flowers, cooked them some food, and made them quantities of chocolate, which is the best of their drinks.’

Pagden contends that the framing of Montezuma (a name variously rendered by historians as Moctezuma, Moctezoma, Motecuhzoma, etc.) as semi-divine and all-powerful ruler of an empire was a part of Cortés’ propaganda effort, intended ‘to create the image of a wholly intelligible, virtually European, political order, one which would allow his readers to see his deeds in the light of those of the heroes of the Roman histories and the warriors of the Reconquest [of Spain].’ Research now suggests that while what is popularly known as the Aztec Empire certainly did make war on and extract tribute from settlements across a huge area, it was more of a loose federation and not so centralised as the European polities it was compared to.

Díaz, as the passages above indicate, treats Montezuma more or less as Cortés does: his possessions vast, his bearing noble, his warriors fierce. The Conquest of New Spain can be read as a heroic tale, a boys’ own adventure, with pitched fighting, cunning schemes and legendary treasures to be won.

‘We left the camp with our banner unfurled and four of our company guarding its bearer, and before we had gone half a mile we saw the fields crowded with warriors, with their tall plumes and badges, and heard the blare of horns and trumpets. What an opportunity for fine writing the events of this most perilous and uncertain battle present! We were four hundred, of whom many were sick and wounded … When they began to charge the stones sped like hail from their slings, and their barbed and fire-hardened darts fell like corn on the threshing floor, each one capable of piercing any armour or penetrating the unprotected vitals.’

Not All is Fair in War

Though the valour of the enemy and the danger to which the Spaniards were exposed are frequently mentioned, there comes a point when the reader can’t help but become a little sceptical. The conquistadors win most encounters handily, only a few men killed against dozens or hundreds of Mexica casualties.

Another chronicler, Bartolomé de las Casas, gave the reason for this as follows: ‘war in the Americas is no more deadly than our jousting, or than many European children’s games‘. While he was prone to exaggeration himself (in a considerably better cause, spending much of his life campaigning against the depopulation and enslavement of the peoples of the Americas) there is something in this.

Inga Clendinnen, in Aztecs: An Interpretation, her wonderful evocation of that culture, points out that:

‘While the Mexica had projectile weapons, their use belonged to the preliminary stages of battle, being aimed rather at demoralization than death. Their lack of penetrating power is indicated by the invading Spaniard’s abandonment of their own metal armour in favour of the quilted cotton of the Indians. The matched duel with obsidian or flint-studded “swords” was the preferred mode of combat, with the long shallow blades designed to incapacitate rather than to cut deep: Mexica warriors sought captives, not corpses.’

The conquistadors did suffer and were risking their lives. Díaz writes, after witnessing from afar the disembowelling of his captured comrades, ‘I came to fear death more than ever in the past. Before I went into battle, a sort of horror and gloom would seize my heart, and I would make water once or twice and commend myself to God and his Blessed Mother.’ Nevertheless, the Mexica mode of war gave away an enormous advantage.

That the Mexica continued to fight in their stylised manner to the end, even as the bodies were piling up in the streets of their capital, may seem strange, even stupid. Theirs was a society built on a warrior ethos, and so bound by notions of honour, which can be very powerful. Clendinnen tells us that they had a regular ‘season of war’, between harvest and planting. But we have our own customs and taboos of war, which seem unremarkable until they are contrasted with others.

In 1937 the Basque town of Guernica was bombed to utter ruin. The Nazi Luftwaffe carried out the attack on behalf of Spanish fascists who had made war on the democratically elected government. It was an act of unprecedented cruelty, the first air assault on a civilian population, and the League of Nations passed a resolution aiming to prevent future atrocities of the kind. When Pablo Picasso heard what had happened, he painted the famous work that has become an international anti-war symbol.

However, World War II followed soon after, and the Allies joined the Axis powers in using indiscriminate aerial bombardment of towns and cities as a weapon of war. As a result, at the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials no one was prosecuted for this crime, and it has since become normalised as part of modern warfare. Chemical weapons, on the other hand, are prohibited under the Geneva Protocal.

This has led to a situation in Syria where the use of chemical weapons to indiscriminately murder civilians is considered unconscionable and a ‘red line’, whereas the long term use of explosive and incendiary bombs to indiscriminately murder civilians is distressing, but attracts less opprobrium, because it’s close to the way that ‘we’ make war (on an industrial scale in Vietnam and, most recently, when Raqqa was razed to the ground during the campaign against ISIS). Even if we faced defeat, it’s possible we would still refuse to use chemical or biological weapons.

Greed Raised to Mythic Proportions

The attempts by Cortés and Díaz to cast the peoples they conquered as powerful, united and dangerous served both to enhance their glory and to legitimate their rule. Las Casas was well aware of that, hence his downplaying of the military challenge that the Mexica presented and his lurid focus on Spanish wrongdoing. Indeed, Díaz takes him to task for suggesting that they had ‘punished the Cholulans for no reason at all, or just to amuse ourselves and because we had a fancy to.’ This ‘punishment’ was a massacre, excused in the eyes of the conquistadors because, they said, they had discovered that their hosts were plotting to attack them.

Whatever the truth of that is, Díaz and his fellows had played a large part in contriving a situation whose logic could be conceived of as ‘massacre or be massacred’. No doubt he and his companions felt themselves morally justified in overthrowing, even violently, a culture so unchristian as to carry out human sacrifice. Early in their expedition, the leader of a conquistador scouting party reported finding in a temple:

‘the bodies of men and boys who had been sacrificed, the walls and altars all splashed with blood, and the victims’ hearts laid out before the idols … [He] told us that most of the bodies were without arms and legs, and that some Indians had told him that these had been carried off to be eaten.’

This is deplorable, and it isn’t hard to understand that the ‘soldiers were greatly shocked at such cruelty.’ Yet their mission was undertaken in bad faith. Prescott translates a passage in which Díaz manages to weave together the inhumanity of the conquered, the nobility of the conquerors – and the venality of their motives:

‘Where are now my companions? They have fallen in battle or been devoured by the cannibal, or been thrown to fatten the wild beasts in their cages! They whose remains should rather have been gathered under monuments emblazoned in letters of gold; for they died in the service of God and of His Majesty, and to give light to those who sat in darkness – and also to acquire that wealth which most men covet.’

It is good that the practice of human sacrifice disappeared from the Americas. But when the motive was the desire for land, slaves and gold, and the means was a war that ended with Díaz unable to walk in the defeated capital ‘without treading on the bodies and heads of dead Indians’, it’s difficult to raise a cheer.

Throughout the adventure, the conquistadors squabble over the spoils, principally concerned with gold. Díaz suggests that Cortés held back some of the ‘royal fifth’ of loot that was by law the lot of the King, not to mention portions of his men’s share. Following their victory, Cortés and many of his men lodged in a palace with whitewashed walls amenable to graffiti. For days on end messages appeared in prose and verse questioning the leader’s ambition and greed: ‘My soul is very sad and will be till that day / Cortés gives us back the gold he’s hidden away.’

Some of the conquistadors made nothing from the conquest. Says Díaz, ‘Many of us were in debt to one another. Some owed fifty or sixty pesos for crossbows, and others fifty for a sword. Everything we had bought was equally dear. A certain surgeon … who tended some bad wounds, charged excessive prices for his cures … and there were thirty other tricks and swindles for which payment was demanded out of our shares.’ Their purchases were made on credit, indeed, the expedition as a whole was largely paid for by the promise of the riches it would yield.

As a result, Díaz and others among his companions immediately set off to find wealth elsewhere on the continent. Cortés himself, some years later, was all but bankrupt and had to return to Spain, where he appealed to the King for relief from his debts.

In Debt: the first 5,000 years, David Graeber, anthropologist and one time member of the Occupy Wall Street movement, argues that debt is why, ‘when dealing with conquistadors, we are speaking not just of simple greed, but greed raised to mythic proportions.’ This might help to explain the unrelenting cruelty of their behaviour.

Díaz recalls his distress when the King’s officials, ‘for greed of gold’, tortured the lord of Tacuba by burning his feet with oil. Still, Díaz recovered sufficiently to help take the lord to find the treasure he eventually confessed was buried at his home. ‘But when we arrived he said he had only told us this story in the hopes of dying on the road, and invited us to kill him, for he possessed neither gold nor jewels.’

Graeber raises the possibility that the collapse in local populations was not only due to European diseases for which they lacked immunity, but may also have been a result of forced labour in gold and silver mines. He quotes Fray Toribio de Motolinia:

‘The bodies of those … who died in the mines produced such a stench that it caused a pestilence, especially at the mines of Oaxaca. For half a league around these mines and along a great part of the road one could scarcely avoid walking over dead bodies or bones, and the flocks of birds and crows that came to fatten themselves upon the corpses were so numerous that they darkened the sun.’

Historically, according to Graeber, people with the power to be so ruthlessly exploitative of others have not usually been so. Something else explains the view of other human beings simply as a means of wealth extraction. Under capitalism, just beginning to emerge around the time of Díaz’s life, debt repayment becomes an imperative, creating social structures that require exploitation.

If you are my neighbour and I see that you aren’t in a position to return a favour of goods or services that I’ve given you, I might be annoyed, but I probably won’t make unreasonable demands. When credit becomes a chain that spreads halfway around the world, those who have extended it are insulated from any human costs of the interest they expect to receive. The conquistadors owed money and were legally and morally obliged to pay it back to people on the other side of oceans, who saw no corpse-fattened crows, only the profits and losses in their ledgers.

The conquistadors were driven by, in Graeber’s words, ‘the psychology of debt … the frantic urgency of having to convert everything around oneself into money, and rage and indignation at having been reduced to the sort of person who would do so.’

Elegy in Flower and Song

Despite its sordid motives, this is a truly epic tale. Much of the interest lies in guessing how much in it is true, how much embroidered – whether as outright propaganda, by Díaz’s ignorance of his own motives, or through his interpretation of Mexica behaviour.

But the real power of The Conquest of New Spain lies, for me, in the veiled elegy it is for a lost civilisation. Kissam and Schmidt’s collection Flower and Song (a Mexica formulation meaning ‘poetry’) renders one of the Mexica’s own elegies:

We mourned for ourselves, our lot.

Broken spears lie in the by-ways,

we have torn out our hair by the roots.

Palaces stand roofless, blood-red walls.

Maggots swarm the squares and huts.

Our city walls are stained with shattered brains.

…

Our strength was in our shields

but shields could not resist this desolation.

…

The lament extends like a cloud

and on the market town tears fall.

Already the Mexicans have fled across the lake.

They are like women. Everyone flees.

‘Where are we going?’

‘Oh, friends!’

and later,

‘Has it happened?’

They have abandoned the capital already.

Smoke rises, the mist

is spreading.

Weep, my friends,

and know that by these deeds

we have forever lost our heritage.