I Put a Spell on You

John Burnside

2014

The title of this book is drawn from the song of the same name, popularised by Nina Simone, though originally, and beloved of Burnside, sung with eccentric power by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. But as well as a referent, the title may stand as a statement of the author’s intent.

Burnside is concerned with magic, though as the word ‘magic’ has lost its magic, he prefers the Scots terms glamourie and thrawn. His writing – poetry, fiction, and in this case memoir – is an attempt to evoke the world as it is beyond our reasonable packaging of it into manageable chunks of sensible procedure such as ‘career’, ‘dating’, ‘property market’, or ‘golf’. It is about ‘a sudden and sometimes

frightening openness, the soul like a door ajar … the physical world immediate and

intimate and erotic, invested with new energy and light and, at the same time,

beautifully perilous.’

He knows well its perilous aspect, an occasion of which is described in the second of his three memoirs, Waking Up in Toytown. He recalls having woken up, disoriented, naked, watching himself in the mirror, conscious that he has created some ritual to ward off the two-day old terror of a nightmare he no longer clearly remembers, and seeing:

‘…a laminate wardrobe … crammed with clear glass bottles … all of them full almost to the brim with the same sweet-smelling dark gold liquid that can also be found in the dozen or so bottles that have been placed at precise intervals around the bed. This liquid is a mixture of blood, honey, alcohol, olive oil and urine; [there is] a single feather, balanced precariously on each rim. If one feather falls, then the spell fails’.

Since then, Burnside has spent time in hospital recovering from severe apophenia: the metastasising inference of pattern and meaning, such as when one sees a face in a cloud, or a gambler believes that after three red, three black, two red, two black, the roulette wheel must yield her colour next. Or when you come to realise that the promotional blurb on the side of cereal packets contains a coded series of instructions guiding you to your destined role as prophet of the New Age.

For a time, Burnside moved to suburbia, worked in IT, gardened. This, he thought, would make him normal. Fortunately for us, he kept writing all the time, and eventually realised that entering a ‘Surbiton of the mind‘ was no panacea for his mental illness. He accepted the danger of opening himself to the world again.

I Put a Spell on You has at its core a summer romance in which its author fell in love with a girl, but, when she kissed him, told her it was a mistake. Why, strange to himself, did he reject what he most wanted? This book is the beginning of an answer.

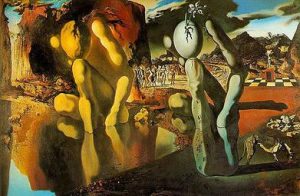

Narcissus: the First Painter

Part of that answer lies in an idiosyncratic theory of painting put forward by man of the Renaissance Leon Battista Alberti. His book De Pictura, as well as giving the earliest set of rules for drawing with accurate perspective, argued that Narcissus, the legendarily beautiful Greek who fell in love with his own reflection, was the inventor of painting: ‘For what is painting, if not an attempt, through the discipline of art, to embrace the surface of the pool in which we are reflected?’

In Ovid’s telling of the tale, Burnside emphasises, ‘When Narcissus sees the beautiful youth in the pool, he does not know, at first, that it is his reflection.’ He goes on: ‘In that first glimpse, he loves what he sees; only later does he understand that what he loves is actually himself. Having believed himself to be alone, looking out at a world that was separate from him, he all of a sudden sees that he is in that world.’

In Burnside’s idiosyncratic treatment, ‘Narcissism’ as overweening self-regard has nothing to do with Narcissus, who after all rejected the nymph Echo because through her he only heard himself. If, in the pool’s reflection, ‘he had not recognised himself in this world, he could have lived forever in his solipsistic state’, a state reinforced by Echo’s repetitions. Now he is aware of himself as an object among others, and as such subject to death. He has seen ‘the image of himself in a world that is neither echo nor reflection’ and is opened to the possibility of ‘real love … and the beginning of that discipline is to acknowledge the mystery of, and to choose to love, oneself.’

The work of many artists can be considered variations on a theme, and Burnside takes no great trouble to conceal his themes. This discussion of Narcissus echoes that of a character in his 2011 novel A Summer of Drowning. There, a version of it is told to the protagonist, Liv, a thrawn young woman who lives with an unfinished painting of herself. Her mother, a famous artist, told her that ‘something isn’t working’, but hung the thing up anyway, and by now Liv doesn’t ‘see the girl it depicts as me any more’.

The novel as a whole is about Liv’s inability to recognise her self in the world, and the terrible danger this spells both for her and for those around her. She spends her days on Kvaløya, an island in the far north of Norway, watching others, often through binoculars, ‘one of God’s spies’. But when others look back… ‘he was staring straight at me, yet he saw nothing. Nothing and nobody.’

This inability is one that Burnside has lived, as we learn from another echo bouncing between his books. In A Summer of Drowning. Liv takes a trip, and is given a mysterious note (quoting the Christian mystic Thomas Merton) that someone has left for her at the hotel reception. No one but her mother knows where she is, and when she quizzes the reception staff she suspects them of playing a game with her. Who on earth has done this?

In I Put a Spell on You, Burnside tells a similar story of his own:

‘…the phone would ring but, when I picked it up, there was nobody there, just a faint noise that sounded like surf rolling on a shingle beach, far in the distance. To begin with, I would ask this empty line over and over again who was calling; if I was in a hotel, I would call the front desk and demand that some embarrassed receptionist trace my last caller. After a few weeks of this, I began to understand that the calls weren’t real, that they had to be hallucinations … I kept on listening for that voice through the sound of the waves, a voice I had taken for a bird call, but eventually concluded was something else, something like my own voice, calling me from a pit town in the snow, trying to tell my future self, through a decades-long wash of static and monochrome, that everything had to change.’

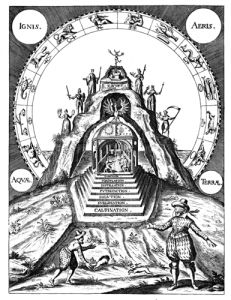

Two Ways of Seeing

Looking out only, unreflective, is animal. The world seen that way lacks depth, and, in that condition, if we are to see anything of ourselves it must be out there in what we’re looking at. In Psychology and Alchemy, Carl Jung considered that proto-science as a projection of its adepts’ psyches. Often working in secret and alone, to avoid the scrutiny of the Church, immersed in the intoxicating fumes of their combustible experiments, they watched in deep concentration for a treasure to emerge. For Jung, what they witnessed and described was frequently the unfolding development of their own selves. This occurred with more or less self-awareness on the part of the practitioners, some explicit that the successful reaction required a transformation in the alchemist as well as the alembic.

This cabbalistic approach prevails, well, in Kabbalah itself, of course, and in general exegesis of religious texts, as when whole sermons are spun out of single – and often unpromising – sentences of the bible. Divination of all kinds – whether the reading of esoteric tomes, entrails, or tea leaves – also involves this projection of the self. If less so than some cynics claim, literary theory can succumb to it too, so I’d best watch my back.

‘Every thing possible to be believed is an image of truth’, said Blake, and while it’s clear that the literal connections of these hyper-interpretative practices may be tenuous, often something of value is produced – though that value may have been fished up out of the depths of the interpreter’s meditative attention, as much as, or more than, from the thing attended to. But Blake’s Proverb of Hell cuts two ways, for if it says that even the most outlandish beliefs contain something that relates to truth, that as such we can learn from them; it says also that even our most settled beliefs are no more than images of truth.

Hence we have eccentric visionaries like Burnside, who reject socially endorsed reality, which he calls ‘the Authorised Version’, in favour of the thrawn, of glamourie. His character Liv speaks for him when she describes two ways of seeing. ‘The first is the way we learn from infancy onwards, the way of seeing what we are supposed to see, building the consensus of a world by looking out for, and finding, what we have always been told is there.’

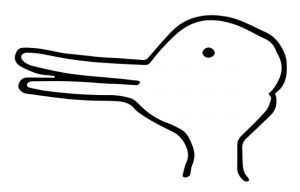

And this is, literally, how we see. Wittgenstein used his famous duck-rabbit to illustrate the case:

The image can be seen as a duck, or as a rabbit, and we can switch from seeing one to seeing the other, though the image itself never changes. What we don’t see is a line and a dot. This is the case with almost everything we look at: we do not just see something, we see it as something. That collection of bricks and glass is a house, this skeletal wooden framework is a device allowing me to sit down comfortably, those quickly shifting dots in the sky are a flock of birds. Without the concepts ‘house’, ‘chair’, ‘flock of birds’, although I would see the same phenomena, it wouldn’t be possible to see them as a house, chair or flock. If I had never seen a rabbit, I couldn’t see the duck-rabbit – only the duck.

Our seeing is infused with our expectations. The psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott believed that perception is a creative act. When you look at a clock on the wall, you create the clock – though you are usually careful to only create clocks where there actually are clocks. This may sound ridiculous, but think of the possibility that occasionally you might create a clock in the wrong place – only to discover that what you saw as a clock you now see as a suggestive set of shadows in a room lit only by moonlight. You have switched from the one perception to the other as from the duck to the rabbit.

If this is so far too mystical for your taste – glamourie, divination, metaphysics – consider the view of neuroscientist Anil Seth: ‘we’re all hallucinating all the time; when we agree about our hallucinations, we call it “reality.”‘ Or we might call it ‘the Authorised Version’.

The Soul you Disallow

Wittgenstein’s ‘seeing as’ is something like Burnside’s Authorised Version, and what Liv calls the first way of seeing. The second way of seeing is perilous and beautiful. It looks beyond the ordered and agreed human world to the wild. It creates new expectations. Liv has ‘seen through the fabric of the world everyone else agrees upon’ and is scarred by that ‘terrible privilege’. If you’re not careful you’ll end up surrounded by bottles of blood and piss, feathers everywhere. But this is the way the poet looks too, and if you look long enough, pay enough attention, you might just catch a glimpse…

‘of something

at [your] back,

not heard, or seen,

but felt,

the way some distant

shiver in the barley registers,

before [you] can think to say

it was never there.’

And who knows but that this something seen and not seen might have been ‘the true self walking away through a woodland clearing’. The lines are taken from Black Cat Bone, a collection that won Burnside both the 2011 Forward and T.S. Eliot prizes, this last from the poem Bird Nest Bound.

The longer section is from The Fair Chase, which condenses Burnside’s preoccupations. Its protagonist begins stuck in the Authorised Version of reality on a hunt for he’s not sure what with his father’s friends: ‘with my father’s gun / bound to the old ways, lost in a hand-me-down greatcoat’. He looks for a way out, peering into water, Narcissus-like, hoping to meet the eyes of god (who he doesn’t yet recognise as himself) who will curse him with knowledge. There’s nothing doing.

It’s only when he wanders away from the others, ‘flycatcher, dreamer, dolt … alone in a havoc of signs’, that he picks up the quarry’s trail.

‘I never saw it clear, but it was there:

sometimes the brown of a roe-deer, sometimes

silver, like a flight of ptarmigan,

it shifted and flickered away

in the year’s last light

and I came after, with my heavy gun

…

a deer, I thought, and then I saw a fox,

and thinking I knew what it was

I pulled the trigger.’

But whatever he thought to capture isn’t there, could never have been there in so many words, the wild life being outside the trap of language, of the human consensus. The chase has taken him so far from home he has to spend the winter’s night exposed, close to death, ‘unseeing, in a night / so utter, dawn / was like a miracle’. After that, he sees in the second way: ‘I knew the market cross; I knew the spire; / but everything was strange’.

In Burnside’s work there’s often a chase after something just out of reach – and an ambivalence about catching it. In one of a number of essayistic digressions in I Put a Spell on You, he explores Lost Girl Syndrome, the recurrence in art, literature, music and film of dead or disappeared young women who remain the object of male desire. What the Lost Girl symbolises, says Burnside, is what boys lose of themselves when they are forced to become men: that is, when they become socialised according to society’s expectations of them.

So the Lost Girl is something like one’s lost potential, the capture of which might make an ideal self. The concept is close to that Jung reads into the coniunctio. This stage of the alchemical process is a union of opposites – imperfectly realised in the adepts’ shoddy chemistry, but illustrated in treatises as a union of male and female. Jung saw this as like the psychological process he worked to encourage: the incorporation through psychoanlaysis of our unfavoured psychic capacities, usually symbolised as male for women, female for men (though in our time particularly there is potential for these symbols to be queered). The figures of the coniunctio were often incestuous, a sign that the union envisaged may indeed have been of estranged parts of the self-same.

And some of the alchemists also knew they were working with two ways of seeing. Jung quotes Gerhard Dorn:

‘There is in natural things a certain truth which cannot be seen with the outward eye, but is perceived by the mind alone, and of this the Philosophers have had experience, and have ascertained that its virtue is such as to work miracles.’

Perhaps we could recast apophenia as a generic term for the externalised study of the self.

Returning to Narcissus, Burnside argues that love is powered by lack – we aren’t everything we want to be so we look elsewhere to fill the gap. Wanting, not possession, is the pleasure of love.

‘Thus, the only way to perpetuate such love is to be forever on the point of possession … Assuming this argument holds … Narcissus can be said to have found in his image the perfect Beloved, one he can neither possess nor lose’.

The chase need never end. Seeing this love as for one’s own other self, oneself as an object, allows others to be loved for their separate selves. But despite the glamour of this argument, the shadow of solipsism remains. Elsewhere, Burnside has written: ‘To be in love and to say nothing about it – this seems to me the most elegant (and perhaps the only sensible) form of romantic attachment.’

Burnside’s Lost Girl was Christina, who he rejected through naivety and fear, but also through a confused sense that to be with the flesh and blood Christina would not be to catch the Lost Girl Christina he saw her as, the lost part of himself. The older Burnside, seeing more clearly that the Lost Girl will, though sometimes glimpsed, never quite be caught, knows that he needn’t have neglected the ‘real’ Christina for her sake:

‘I wish I’d known back then that it wasn’t us I loved, but something abroad on the meadows, a swim of warmth that held us for an instant, as it flowed from here to there, the way the sun swims across a mile of ripening wheat then darkens in the local sway of matter.’

Hallucinatory Illumination

Love, to be sure, can be seen as projection, illusion, hallucination, but it’s no more hallucinatory than any other of our perceptions, and like them, it may also, on occasion, be accurate. When something in the wild world unexpectedly marries up with the hallucinatory power of love, something till then unknown comes into focus for a moment – and we should pay attention.

At the close of A Summer of Drowning, Liv finds that she has a reason for living:

‘To pay attention. There was some ancient Mexican tribe whose members took turns each night to watch the sun go down and then waited in vigil through the dark till it returned – and they never assumed that it would, they never took that light for granted. They took turns to stand watch, and they believed that the real reason why the sun reappeared each day wasn’t to do with gravity, or how the earth turned on its axis. They thought it was their attention that drew it back – and I live in that same state of attention, day and night.’

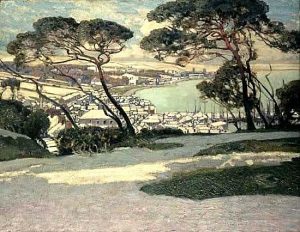

She watches so carefully because she knows that there’s something beyond the Authorised Version, ‘there are tiny, infinitesimal loopholes of havoc in the given world that could spill loose and catch me out wherever I am.’ Liv has suffered, and has reason to be cautious, but opening oneself like this is, remember, beautiful as well as perilous. What we can gain is described in I Put a Spell on You in relation to the painting of Alfred East:

‘What was rich about these paintings was the colour. It was as if someone had reached up and found the switch that turned the lights on in my everyday world – everything was deeper, stronger, more erotic. In an Alfred East painting, things looked the way they looked on LSD. Not so much strange as new. Not dreamlike and not at all unreal. Things were as they were, only more so, like the objects and animals in an illuminated manuscript … [On LSD] there was a new sense of things being lit from within, and there was so much detail to my surroundings that I felt I was in danger of being overwhelmed by it all – and then I was overwhelmed. Everything – colour, sound, form, light – was more vivid than it had ever seemed before, yet I didn’t think of this vividness as an illusion brought about by the drug. On the contrary, I knew, without a doubt, that this was how things really were, and that I had simply lost, or perhaps never gained, the ability to see.’

I think to have seen something like this myself, on the odd occasion, though without the medium of LSD. The alchemists talked of it too: ‘This light is the true light of nature … It is in the World and the whole edifice of the World is beautifully adorned … by it … which the World has before its eyes yet knows it not.’ I have tried at times to say it in my own words, but words can never quite capture that wild light:

The night still as depths

remembered from perfect eyes,

whose treasure transfers

to street-lit trees.

The sodium glow falling

golden on shadow flecked leaves

silhouettes the proudly standing fount

that springs energy from earth to air,

a slow motion roman candle.

This trunk, among brick buildings

and sunk in concrete,

seems so at home

the houses hide behind it.